How many different types of guitar chords are there? Chances are, you already know how to play a bunch of different chords. You have probably learnt how to play them by associating different shapes and fingerings with different chord names. But you’ve probably also come across some chord symbols that look like hieroglyphs and have wondered from time to time, what do all these symbols and add-ons actually mean?

That’s what we’re going to try to break down in this lesson. In some ways, ‘figuring out’ chords is relatively easy. There are some obvious applications of numbers and labels that happen. The B Major 6 chord, for example, is made up of the B Major chord, as well as the 6th note of the Major scale. But some labels are not as obvious.

This lesson is not for the faint-hearted. We are going to cover a lot. But by the end of it, you should have the ability (or at least a one-page reference guide) to figure out any chord that you come across. Before we go into too much detail though, we need to go back to the basics and start from there.

Table Of Contents

- Guitar Chord Rules

- Triads – Just Stack Thirds

- What Is The Major Chord?

- What Is The Minor Triad?

- Doubling Up, Changing Octaves, and Moving Notes Around

- Augmented And Diminished Triads

- What Are 7th Chords?

- The Eight Most Important 7th Chords

- What Do The Numbers In Chords Mean?

- Obscure Chords

- Summary

This lesson is part five of a series of lessons on chords. In the first few lessons, we looked at basic open chords, then went onto bar chords, suspended chords, and jazz chords. If you’re new to chords, it would be worth going back and reading those lessons. The preceding lessons are more of a practical guide to learning chords – in which order should you learn them and how they fit in to rough categories.

This lesson is very much theory based. We’re going to look at how to deconstruct chord labels, both simple and complex, so that you will know which notes should be included in each chord. While we will use some chord diagrams, the purpose is to help you understand how to build chords yourself. Hopefully, by the end of this lesson, you will be able to look at a chord label, and figure out how to play it, by building the chord yourself.

To do this, we need to go back to basics. Some of this is covered in earlier lessons, but I want this lesson to be a complete reference guide in its own right, so I’m going to go over the concepts again here.

Guitar Chord Rules (and Disclaimer!)

It’s worth mentioning that there are some grey areas when it comes to chord construction, especially when dealing with the guitar. We will explore some of these areas more as we go, but keep in mind that the nature of playing chords on the guitar means that some rules and variations are kind of specific to the guitar itself. If you have a PHD in chord theory, and you are reading this, I apologise.

Having said that, the following (unofficial) rules will help you navigate through some of the confusing aspects of chord construction. I’m going to simply state what these rules are, and then come back to them at relevant points throughout the lesson:

- Rule #1 – You can change the order of notes.

- Rule #2 – You can double up on notes.

- Rule #3 – You can change the octave of notes.

- Rule #4 – You can leave out notes.

Learning about chords is a mixture of logic and seemingly arbitrary rules. I compare this to learning how to spell words in English. If you hear how a new word sounds, you can probably guess what the spelling of the word is, with a reasonable degree of accuracy, but sometimes you come across exceptions. The same goes with chord names.

Lesson Breakdown

Because this is such a long lesson, it will be useful to provide a brief overview of how this lesson will be structured. The following outlines the three main categories of chords that we will explore.

- Triads – Triads form the basic chords that most people know and use pretty much all the time (Major and minor) as well as a few which are less used (augmented and diminished)

- 7th Chords – When you stack an extra 3rd on a triad, you get a 7th chord.

- Extensions (2s, 4s and 6s) – 7th chords include the chord tones 1, 3, 5 and 7 (or alterations of those chord tones). That only leaves 2s, 4s and 6s. These chord tones (and alterations of them) can be added to chords, to form extensions.

Triads – Just Stack 3rds

To understand how chords work, you need to understand what triads are. Triads are simply three-note chords, built from the Major scale, by stacking thirds. This means that you also need to understand what the Major scale is. If you don’t, I suggest you go and read this lesson on Major scales here.

As a brief summary, the Major scale is a 7-note scale that determines the notes inside a given key. It is effectively the ‘master scale’. For example, the C Major scale contains the following notes:

- C – D – E – F – G – A – B

Therefore, the notes in the key of C Major are:

- C – D – E – F – G – A – B

The D Major scale contains the following notes:

- D – E – F# – G – A – B – C#

Therefore, the notes in the D Major scale are the same.

And so on it goes. For a quick reference, here is a chart of all 12 Major scales:

The first 12 scales are all of the ‘standard’ Major scales that exist. The bottom 3 scales are the enharmonic equivalent scales. For Example, Ab Major is enharmonically the same as G# Major, but we use Ab Major much more than G# Major. Bb Major is enharmonically the same as A# Major, but we use Bb Major much more than A#. And so on..

But back to triads…

What is the Major Chord?

The most common triad is the Major triad. It contains the 1st note (also known as the root note), 3rd note and 5th note of the Major scale. These numbers are also referred to as ‘chord tones’. Each note is considered a ‘3rd’ away from the next one, so producing chords in this way is known as ‘stacking thirds’.

Here’s a visual example, using the C Major scale:

All you really need to know is that stacking thirds produces chords that sound good and usable (as opposed to stacking 4ths, for example, which can sound a bit weird and ‘out there’).

Whenever we play any Major chord, we are actually playing the Major triad.

Not only this, but we actually abbreviate Major chords even further. Because the Major chord is the most commonly used chord, we often abbreviate Major chords to just the root note.

- Instead of saying C Major, we usually just say C.

- Instead of saying Bb Major, we usually just say Bb.

But in all of these instances, we are playing the Major triad. Just three notes.

Let’s do a few more examples:

Let’s ‘figure out’ the A Major triad:

The A Major scale has the following notes

- A – B – C# – D – E – F# – G#

Therefore, the A Major chord has the following notes (1 – 3 – 5)

- A – C# – E

What about the Bb major triad:

The Bb Major scale contains the following notes:

- Bb – C – D – Eb – F – G – A

Therefore, the Bb Major Triad (1- 3 – 5) looks like this:

- Bb – D – F

What is the Minor Triad?

To figure out the minor triad, we still use the Major scale as our reference point. This is why you can think of the Major scale as the master scale. The minor triad contains the following notes of the Major scale:

- 1 – b3 – 5

The ‘b3’ (“flat 3”) simply means that we lower the 3rd note of the Major scale by a semitone (or the equivalent of one fret).

Let’s figure out the A minor triad.

A Major Scale:

- A – B – C# – D – E – F# – G#

A minor triad (1 – b3 – 5):

- A – C – E

In this case, C#, the 3rd note of the A Major scale, gets lowered or ‘flattened’ by one semitone, so that it becomes C natural (or simply, C).

Another example with the Bb minor triad:

The Bb major scale contains the following notes:

- Bb – C – D – Eb – F – G – A

Bb minor triad (1 – b3 – 5):

- Bb – Db – Eb

So you now know how to construct the Major and minor triads. By being familiar with Major scales (or using the Major Scales chart above), and knowing the properties of both the Major (1 – 3 – 5) and minor (1 – b3 – 5) chords, you can figure out any Major or minor chord that there is. That might not seem like much, but these chords are super important for a few reasons. Firstly, the Major and minor chords are easily the most common chords. I haven’t done a statistical analysis, but if I did, I’m sure I’d find that the basic Major and minor chords are used around 80 percent of the time. Maybe even more, depending on the style of music.

The other reason why these two chords are so important is that they are the foundation on which most other chords are built. When we play a minor 7 chord, or a Major 7 chord, or a minor 9 chord, we basically take the Major or minor triad and add notes to it. Even when we alter notes within the triad, for chords such as the diminished chord, we can still think of using the Major or minor triad as the starting point, and then alter notes to get the desired chord. The Major and minor triads form the ‘core’ of just about every chord.

We’ll get back to that. But first, let’s take a slight detour.

Doubling Up, Changing Octaves, and Moving Notes Around (Rules #1, #2, #3)

This is something that we’ve already covered in this lesson series so far, but it’s vitally important to this lesson, so we’re going to go over it again.

One thing that you need to get your head around when learning chords on the guitar, is how we deal with the ‘numbers’ (chord tones) inside every chord.

In a very basic way, all chords can be identified by the notes (or altered notes) of the Major scale. With the Major triad (the one we just looked at), we have the chord tones 1, 3 and 5. This means that if you take the 1st, 3rd and 5th notes of the Major scale, for any given root note, you have your Major chord. This would be very easy to demonstrate on a piano, because the notes are set out in a very predictable and orderly way. The problem (although it’s not really a problem) with guitar, is that it is set out in such a way that we rarely play the basic version of any given chord.

Instead, what we do is change around the order of notes (Rule #1), double up on notes (Rule #2) and play different octaves of certain notes (Rule #3).

Here is an example.

The E Major scale contains the following notes:

- E – F# – G# – A – B – C# – D#

Therefore, the E Major chord (1 – 3 – 5) contains the following notes:

- E – G# – B

Yet, the most common way to play the E Major chord on the guitar is as follows:

You’ve probably played this chord before. If we look at the notes in the chord (from the 6th string to the 1st string), we have the following:

E (1), B (5), E (1, up one octave), G# (3, up one octave), B (5, up one octave), E (1, up two octaves)

As you can see, there is no logical order to the way that the 1, 3 and 5 are organised. We can basically double up on any notes that we want, and play each of the notes in any octave.

This shouldn’t be too confusing. At the end of the day, all I’m really highlighting is that you can play the notes of a chord in whichever octave you like, and you can double up on notes as much as you like. It’s very important to acknowledge these rules nice and early however, because they’ll become increasingly relevant as we keep exploring chord labels.

What Are Augmented and Diminished Triads?

We’ve covered Major and minor triads. Let’s look at the other two types of triads – augmented and diminished.

Both chords are triads (3-note chords). Again, we reference notes from the Major scale:

- Augmented – 1 – 3 – #5

- Diminished – 1 – b3 – b5

Just like with all chords, both of these are built, by referring to notes of the Major scale, albeit with alterations (#5, b5 etc).

Also, before I said that the major and minor triads form the basis for just about every chord. This is no exception. The Augmented chord is just a Major triad with a raised 5th. The diminished chord is just a minor triad with a flattened 5th.

While the augmented triad and the diminished triad are not as common as some other chords that we haven’t covered yet, they’re mentioned at this stage of the lesson, because they make up the other two possible triads. Remember, triads are 3-note chords, made up of the 1st, 3rd and 5th notes of the Major scale, or an alteration of those notes.

Therefore, the only possibilities we have are:

- 1 – 3 – 5 (Major triad)

- 1 – b3 – 5 (minor triad)

- 1 – b3 – b5 (diminished triad)

- 1 – 3 – #5 (augmented triad)

Any other possible combinations (such as 1 – b3 – #5) are so uncommon and impractical that we just don’t bother with them. All you need to remember with triads are the four mentioned above. Of course, the Major and minor triads are the most important and most common. You can think of the the diminished triad as a variation of the minor triad and the augmented triad as a variation of the Major triad.

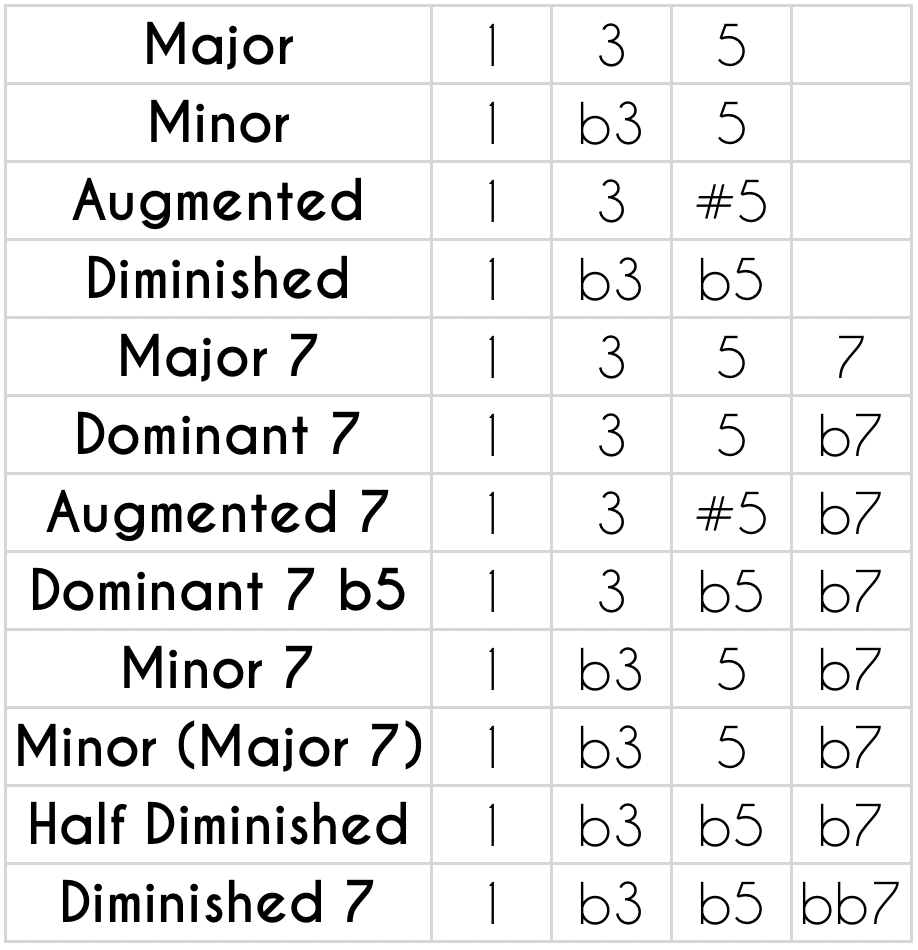

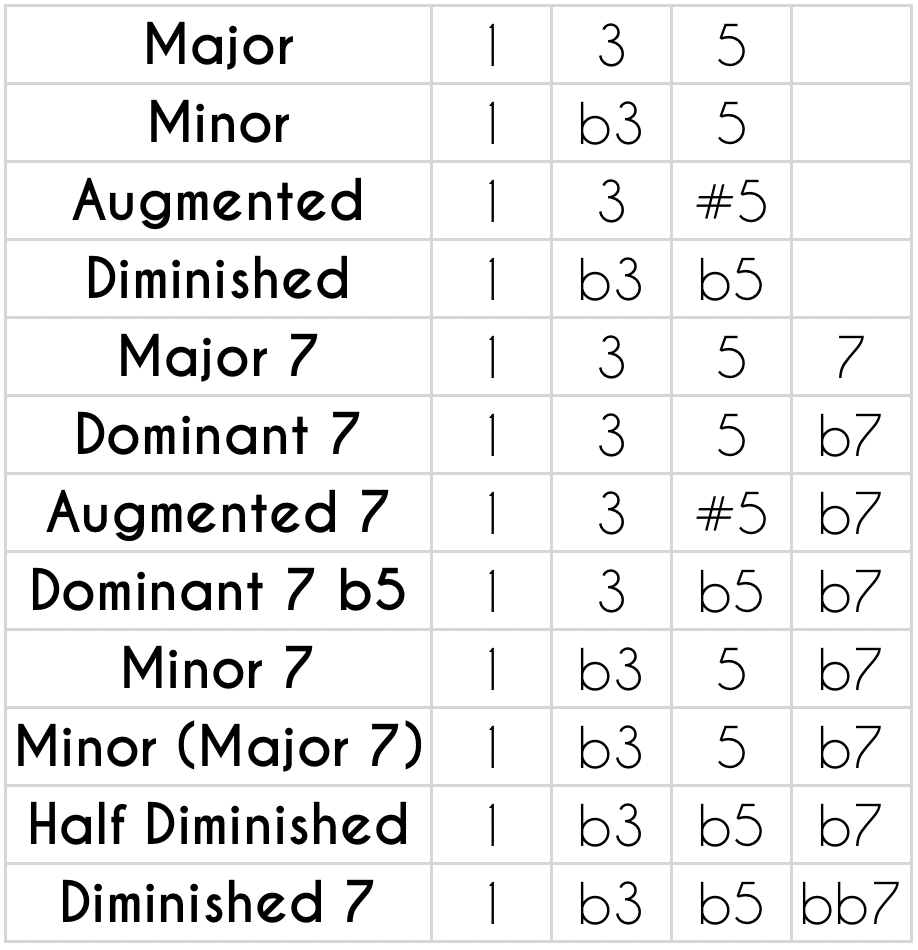

So far, we have the following:

Triads – Chord Tones

How One Chord Can Be Written In Different Ways

A lesson on chord labels wouldn’t be complete without including the variations that occur with the labels themselves. Chord names are often abbreviated, or represented using symbols. The minor chord, for example, is often shortened to a lower case ‘m’, or simply a minus sign (-).

The following chart includes the chords that we have covered so far, as well as different ways that the chords can be referred to. Underneath each chord label (in grey) is an example of how each chord label looks with C as the root note.

Triads – Chord Name Variations

What Are 7th Chords?

We produce chords by stacking notes of the Major scale in 3rds (1, 3, 5). So far, we have only looked at triads (3-note chords). Now we’re going to look at 7th chords. These are chords that have four notes and have some variation of the following chord tones:

- 1 – 3 – 5 – 7

Again, these numbers reference notes from the Major scale.

The most basic 7th chord is the Major 7 chord, which uses the following chord tones:

- 1 – 3 – 5 – 7

The C Major scale contains the following notes:

- C – D – E – F – G – A – B

Therefor, the C Major 7 chord contains the following notes (1 – 3 – 5 – 7)

- C – E – G – B

What we’re going to do now is look at all of the possible 7th chord variations. There are eight in total, but three chords are much more common and important, so we’re going to look a these first.

The Major 7 Chord

We’ve just gone over the Major 7 chord, but here it is again.

- Maj 7 = 1 – 3 – 5 – 7

Because this chord contains an unaltered set of stacked 3rds using the Major scale, you can think of this 7th chord as being a kind of reference point for all other 7th chords.

The Minor 7 Chord

- min 7 = 1 – b3 – 5 – b7

The minor 7 chord is another very important chord, because it is the most common 4-note minor chord. It is in a sense, the ‘master minor’ chord.

It’s worth pointing out another one of those not-quite-logical rules that you may have noticed. We know that all minor chords include the ‘flat 3rd’ of the scale. So it makes sense that the minor 7 chord has a flat 3 in it. But it might not be so obvious as to why the minor 7 chord has a flat 7 instead of just a regular 7. This is something that we could explore further, but at the end of the day, the best thing to do is just remember it as a rule:

The minor 7 chord contains a flat 3 and flat 7.

The Dominant 7 Chord

- Dominant 7 = 1 – 3 – 5 – b7

The dominant 7 chord is usually just abbreviated to 7, for example, we usually say A7 instead of A dominant 7.

Major 7, Minor 7, Dominant 7…

…These are the three most common and important 7th chords. Together with the Major and minor triads, these chords get used roughly 95% of the time (just a guess). You actually don’t need much else, for most Folk/Pop/Rock songs.

The Eight Most Important 7th Chords

As I just mentioned, there are eight 7th chords that are possible (and practical). The most common three are:

- Maj 7 = 1 – 3 – 5 – 7

- Min 7 = 1 – b3 – 5 – b7

- Dominant 7 = 1 – 3 – 5 – b7

Here are the other five:

- Half Diminished – 1 – b3 – b5 – b7

- Augmented 7 – 1 – 3 – #5 – b7

- Minor Major 7 – 1 – b3 – 5 – 7

- Diminished 7 – 1 – b3 – b5 – bb7

- Dominant 7 b5 – 1 – 3 – b5 – b7

The eight chords above are what I would call standard 7th chords. They make up all of the practical, usable variations of 1, 3, 5, 7. Some are much more common than others, but if you learn the above chords by memory, you will have gone a long way to understanding and decoding the often confusing world of chord labels.

Remember, this lesson is focused on theoretical side of chords. If you want a quick guide on how to actually play any of the 7th chords that we’ve just covered, read the previous lesson on jazz chords.

Here is a summary of the 7th chords that we have just covered (as well as the triads):

7th Chords – Chord Tones

7th Chords – Chord Label Variations and Examples

You Can Leave Notes Out (Rule #4)

Earlier, we talked about how as guitarists, we often double up on notes, change octaves around, and change the order of notes. There’s another thing that guitarists do to chords that needs to be mentioned. Omitting notes from the chord. This is done sometimes out of taste, and sometimes out of necessity.

This is relevant now that we’re getting into bigger chords, because the maximum number of notes that a guitarist can play at once is six notes (for six-string guitars anyway).

There are some chords that contain 7 notes, though, so the fact that you can only play six notes means that you would need to omit at least one note when playing such a chord. However, we’re often not just limited by the number of strings. Sometimes, we’re also limited by the notes available in a certain position, or physical fingering constraints.

By leaving notes out of a chord, it does not necessarily mean that the chord becomes something else. Often, because of the context of the chord, our ears compensate for any missing notes.

Think of this in the same way that we abbreviate words, or truncate certain phrases.

Consider the following phrase:

“I’ll be there in 5”

5 what? Days, hours, years? We know that the speaker is talking about minutes. The same thing happens with chords. We can often leave certain notes out of a chords, without sacrificing the the meaning of the chord itself. The techniques involved in doing this are for another lesson (although, if you want to try it yourself, you can experiment and pretty much get the main idea), but all you really need to know is that (especially with larger chords) you don’t always need to include every note for the chord to be valid.

Summary So Far

Everything up until this point has really been one big introduction (sorry about the length). In fact, all of the chords covered so far in this lesson have been covered already in the lessons leading up to this one.

But in a lesson on chord labels, it’s necessary to include this foundational information again. To understand complex chord labels, you need the understand the building blocks that get us there.

Here is another summary:

We build chords by taking the Major scale and stacking notes in thirds. Our most basic chords are the Major triads:

- Major = 1 – 3 – 5

- minor = 1 – b3 – 5

There are also two other, less common triads

- Augmented = 1 3 5

- Diminished = 1 b3 b5

If we add another 3rd onto our basic Major triad, we get a basic 7th chord (which is known as the Major 7 chord)

- Major 7 = 1 – 3 – 5 – 7

There are eight usable variations of 1, 3, 5, 7:

Very common…

- Maj 7 = 1 – 3 – 5 – 7

- Min 7 = 1 – b3 – 5 – b7

- Dominant 7 = 1 – 3 – 5 – b7

Less common…

- Minor 7 b5 = 1 – b3 – b5 – b7

- Augmented 7 = 1 – 3 – #5 – b7

- Minor Major 7 = 1 – b3 – 5 – 7

- Diminished 7 = 1 – b3 – b5 – bb7

- Dominant 7 b5 = 1 – 3 – b5 – b7

What Do The Numbers In Guitar Chords Mean?

If you’ve kept up so far, you will have realised that chord knowledge is largely about numbers. It’s true that context and function play a big role in how chords work together, and why certain chords are labeled the way they are (Major, diminished etc.). That stuff is important, and you can read more about it here, but this lesson is really about the individual properties of each chord. I want you to be able to come across any chord name, and be able to figure out which notes should be included. And that comes down to numbers and labels.

Each chord name is really just a way of indicating which chord tones (numbers) should be included.

Some labels imply multiple numbers (for example, Major = 1, 3, 5) and some numbers are explicitly stated (for example, D Add 9 is a D Major chord with the 9th note of the scale added as well).

These numbers are all references to notes the Major scale or alterations of notes from the Major scale. Once you become familiar with the numbers that are included in the different labels (Major, minor, augmented etc.), you can literally figure how to play chords as you go. Come across a C7b9#11? No problem, just add the right ingredients and you’re good to go.

This is really where this lesson is headed – to be able to give you the rules and principles that will allow you to figure out any chord that you come across. This is not just a cool and useful thing to be able to do, but it’s a great way of exploring the guitar and harmonic concepts. I always feel a bit like a mad scientist when I’m figuring out chords. 98 percent of the time, when I’m playing chords, I’m relying on shapes that I’ve simply memorised and given a label to. The other 2 percent of the time – usually for weird and wacky chords – I enjoy sitting down and trying to come up with a cool way of playing something new.

There are only seven notes in any given Major scale:

- 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

All triads are a variation of 1, 3 and 5.

All 7th chords are a variation of 1, 3, 5 and 7.

Therefore, when we add extra notes to a chord (usually to a 7th chord), there are only three numbers that haven’t already been covered:

- 2s, 4s, and 6s (Extension Chords)

2, 4, 6 – That’s what we’re going to cover now.

Let’s go through each of these numbers and look at how they’re used in chord land:

Chords With 2 (and 9)

Before we start talking about all the ways we can use the ‘2nd’ note of the scale, we need to talk about the ‘9th’ note. Why? Because the 2 and the 9 are basically the same note. Earlier, I said that the Major scale contains 7 notes. This is true, but what happens when we play the Major scale over 2 octaves? We get the following:

- 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7 – 8 (1 octave up from 1) – 9 (1 octave up from 2) – 10 (1 octave up from 3) and so on…

Here’s a visual example, using the C Major scale:

As you can see, ‘2’ and ‘9’ are actually the same note, but one octave apart.

“But wait a minute…”, I here you say. “Didn’t you say earlier that you can change the octave of notes (Rule #3) however you wish? So why have different labels that refer to different octaves of the same note?”.

Good question. The simple answer is that this is one of those annoying grey areas. You can change the octave of notes when constructing a chord (rule #3), but the octave referred to in the labels themselves can imply different things. For example, G6 is a different chord than G13, even though ‘6’ and ’13’ are technically the same notes.:

- G6 = 1 – 3 – 5 – 6

- G13 = – 3 – 5 – b7 – 13

6 and 13 are effectively identical chord tones, yet the label of 13 implies that there is a b7 in the chord, as opposed to the label of 6, which implies that there is no 7 at all.

This is confusing, but at the end of the day, there are only a few of these arbitrary rules.

If you want to be a chord name expert, you need to become familiar with these little idiosyncrasies.

The 2nd note of the Major scale is the same as the 9th note (one octave apart). Now that we know this, let’s look at the common ways that the 2nd note of the Major scale is used with chords.

Suspended 2 Chords

We covered suspended chords (sus chords) in a previous lesson. Basically, the word suspended means that the 3rd is taken out and replaced by another note (either the 2nd or the 4th). The new note is said to be ‘suspended’, because the chord sounds like it wants to resolve back to the regular Major chord (for a few examples, read the suspended chords lesson).

That means that the suspended 2 chord looks like this:

- 1 – 2 – 5

Add 2 and Add 9 Chords

We have already looked at the suspended 2 chord (1 – 2 – 5)

However, we can also add the 2nd note of the scale to the triad, without omitting the 3. This gives us an ‘add 2’ chord:

- 1 – 2 – 3 – 5

Similarly, the add 9 chord has the 9th note of the scale added to the triad:

- 1 – 3 – 5 – 9

Remember how I just said that different octaves in the chord label sometimes imply different things about the chord (G6 is different to G13)? Well here is an example of how different octaves basically refer to the exact same chord. Technically, on a piano (for example), you might use a specific octave (2 vs 9) depending what the chord label was (add 2 vs add 9), but on the guitar, we change octaves (rule #3) and double up on notes (rule #2) so often, that add 2 and add 9 are basically treated the same.

Also, consider this – since we can leave notes out of chords (rule #4), often when guitarists come across add 2 (or add 9) chords, we leave out the 3 (trying to include both the 2 and the 3 can create difficult fingerings), so in practice, add 2 (or add 9) chords should look like this:

- 1 – 2 – 3 – 5

But sometimes end up being played like this:

- 1 – 2 – 5

Which is exactly the same as the suspended 2 chord.

I could keep pointing out these little inconsistencies and confusing idiosyncrasies for the rest of this lesson. But by now you should at least have a clear idea of where the grey areas are, so I’m simply going to go through each label, and tell you what notes should be included.

Let’s keep going with our 2s and 9s.

Remember, 2 is the same note of the scale as 9.

The ‘9th’ chord (for example A9, or D9, or Bb9) contains the following notes:

- 1 – 3 – 5 – b7 – 9

The ‘Major 9’ chord (for example A Major 9, or D Major 9, or Bb Major 9) contains the following notes:

- 1 – 3 – 5 – 7 – 9

As you can see, the difference between the ‘Major 9’ chord and the ‘9’ chord, is that the ‘Major 9’ chord contains a natural 7, while the 9 chord contains a flat 7.

What happens when we alter the 2/9?

b9 and #9 Chords

The 9 of the chord can be altered. When we take a 9 chord (1 – 3 – 5 – b7 – 9), and lower the 9 by one semitone, we get the b9 chord:

- 1 – 3 – 5 – b7 – b9

When we raise the 9 by one semitone, we get the #9 chord:

- 1 – 3 – 5 -b7 – #9

Minor 9 Chords

The last 9 chord that we are going to look at is the minor 9 chord. This is simply a minor 7 chord, with an added 9:

- 1 – b3 – 5 – b7 – 9

Remember, there are certain chords that exist in theory, but just don’t sound good, or have many practical applications.

For example the Major 7 b9 chord. This is a chord that would theoretically contain the following notes:

- 1 – 3 – 5 – 7 – b9

However, it sounds so dissonant that it doesn’t really fall into the category of usable chords. Of course, this is a big, sweeping generalisation, as beauty is in the ear of the beholder. But this lesson is designed to teach you about the chords that you are likely to come across and use. So we’re basically pretending that certain, ‘way out there’ chords don’t exist. By the end of this lesson, you should be able to figure out how to play any of the obscure chords that you might come across, but we’re only going to focus on the ‘common ones’.

Chords with 4 (and 11)

The 4th note of the Major scale is the same as the 11 (one octave apart).

Suspended 4 Chord

Remember that suspended chords mean that the 3rd is replaced by the 2nd or 4th. Therefore, the suspended 4 chord contains the following:

- 1 – 4 – 5

Minor 11 Chord

The minor 11 chord contains the following notes:

- 1 – b3 – 5 – b7 – 11

Major 7#11 Chord

The Major 7#11 chord contains the following notes:

- 1 – 3 – 7 – #11

This chord is a very ‘jazz’ sounding chord. We usually leave out the ‘5’, because it clashes with the #4. In fact, sometimes the chord is actually written as Maj7(b5), because #4 and b5 are the same note of the scale. However, it is most often written as Major 7#11

Dominant 7 Suspended 4 Chord

The Dominant 7 suspended 4 chord (for example, B7 sus 4) contains the following notes:

- 1 – 4 – 5 – b7

Chords With 6 (and 13)

The 6th note of the scale is the same as the 13th note of the scale (different octaves).

Major 6 Chord

The Major 6 is usually written simply as ‘6’. For example, G6, or Db6. It contains the following chord tones:

- 1 – 3 – 5 – 6

13 Chord

The 13 chord (written as G13 or Db13 etc.) is a dominant 7 chord, with an added 13 (or 6):

- 1 – 3 – 5 – b7 – 13

The minor 6 chord is a minor 7 chord, with an added 6 (or 13):

- 1 – b3 – 5 – 6 – b7

Often, we omit the b7, in order to fit the 6 in.

The 6 is rarely altered (b6, #6), because a ‘b6’ is the same note as a ‘#5’, and the ‘#6’ is the same note as the b7, although you will probably come across b6 from time to time, for example, minor 7 (b6).

That’s A Lot Of Chords

So there you have it. We have covered all of the different ingredients that can be used to construct chords. Of course, there are many other combinations of the above notes, that are theoretically possible. We haven’t gone down the rabbit hole of exploring all the different combinations, because most of them are so obscure, that it would be impractical to try to include them all.

Keep in mind though, that if you get your head around all of the chords that we have covered so far, you will intuitively know how to form any of the ‘obscure’ chords not listed here.

This is mainly because because with very obscure chords, they are often labeled very specifically and prescriptively, so as to communicate exactly what should be in the chord. With common chords, we use shortcuts (through names and symbols) to quickly communicate the chord that we’re after. We don’t do this with unusual chords. Instead we effectively spell out everything that is included in the chord. As well as this, these ‘obscure’ chords often contain a recognisable label (such as one of the labels that we’ve covered), followed by altered notes which are placed inside brackets. Which usually means that you can interpret the chord name based on the other labels that we’ve covered and then simply add in any alterations that are specified.

Let’s do some examples of some ‘obscure chords’. Let’s suppose you come across the following chord:

- E minor Major 7 (b9, #11).

This is definitely what I would call an obscure chord. To figure out the notes inside the chord, all we really need to do is take the E minor Major 7 chord (1, b3, 5, 7) and then add the b9 and #11:

- 1 – b3 – 5 – 7 – b9 – #11

Those notes would translate to:

- E – G – B – D# – F – A#

Figuring out how to play it on the guitar would then be another process, but you can see that the more obscure a chord is, the more ‘spelled out’ it becomes.

Which is why we don’t need to cover every possible chord, for you to understand how to figure out every chord.

Here are a few more examples:

- minor 7b5 (9)

This chord would just be a minor 7b5 chord (1, b3, b5, b7), with an added 9 (or 2)

- Sus 4 (b9)

This chord would just be a sus 4 chord (1, 4, 5) with a b9 (or b2) added.

You get the idea. Become familiar with the triads and 7th chords chords that have been covered in this lesson. Then become familiar with the extension chords (2s, 4s and 6s). If you do that, there won’t be a chord out there that you won’t know how to construct.

A Few Common ‘Obscure’ Chords

Even though we have pretty much covered everything, there are a few extra kind of obscure chords that I want to include, just because they get used enough to make them worth being included. They are the honourable mentions in the long list of chords covered in this lesson.

6/9 Chord

This is a great chord that often works in place of a Major 7 chord. It has a really cool ‘acid jazz’ kind of sound. It contains the following notes:

- 1 – 3 – 5 – 6 – 9

9 Sus 4 Chord

The 9 Sus 4 chord is essentially a 9th chord (1, 3, 5, b7, 9), with a suspended 4, which means that we take away the 3, and replace it with the 4. It becomes:

- 1 – 4 – 5 – b7 – 9

It can generally be used in place of a Dominant 7 Sus 4 chord, but has a funkier, jazzier sound.

By the way, I realise that these descriptions are pretty vague, to the point of being worthless. It’s really just a way of introducing the chord. Of course, the best thing to do is play the chords yourself and come up with your own way of describing them.

Half diminished 9 Chord

The half diminished 9 chord has quite a dark sound, but it can be a great substitute for a regular half diminished chord.

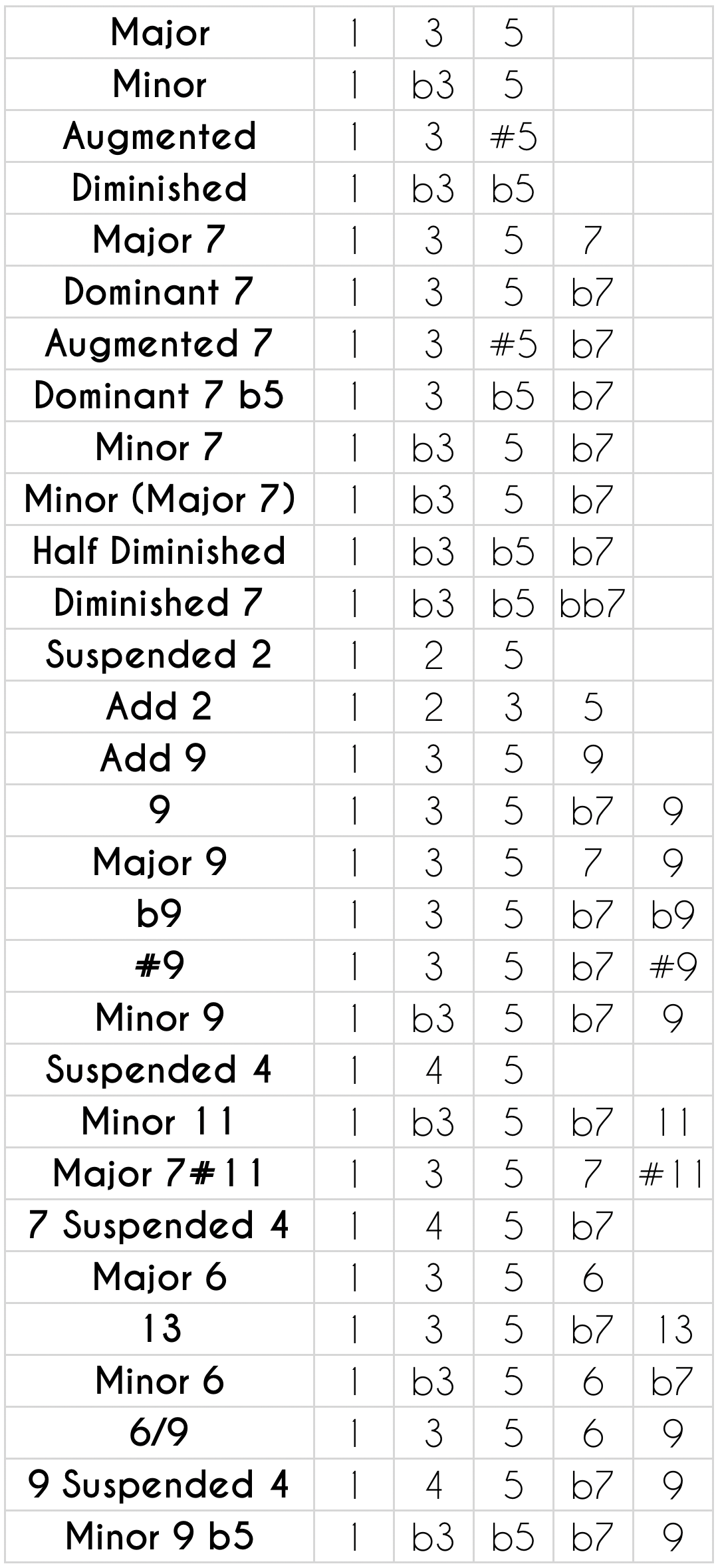

A Summary Of All The Chords We Have Covered In This Lesson

At this point, it’s worth summarising all of the chords we have covered in this lesson. There are quite a lot. The first table is a list of all the chords that we have covered, including their respective chord tones. The second list provides examples of how each label can be written, when you come across it on a page (or screen).

Chords And Their Chord Tones

Chords And Their Different Labels

Experiment With Chords If You Want To Master Them

Experimenting with chords is one of the most effective ways of exploring the guitar and igniting your creative spark. There are many standard shapes that are used for the chords that we have covered in this lesson. You can easily search for them and find out how to play them. But you should challenge yourself to try to figure out chord shapes yourself.

Exploring chords is also one of the best ways to deepen your knowledge of the fretboard, because it requires you to constantly be aware of the notes in any given position. There are many approaches you can use to explore chords. The most simple one is to deconstruct an existing chord/shape. Take a shape that you have come across or you already know and analyse the notes inside the chord. Go through every note of the chord and ask yourself, what note it is (pitch) and which degree of the scale it is. Then try to turn it into another chord by adding to it or modifying it.

Another great approach is to build a chord from the ground up. Pick a random position along the fretboard and try to construct a particular chord by figuring out which notes should be included. You will come up with lots of interesting shapes and sounds. Write them down. They will become part of your library of chords.

This is obviously a massive topic, and we’ve covered a lot in this lesson. You shouldn’t expect yourself to be a chord expert straight away. Hopefully, this lesson demystifies chord construction for you, and acts as a solid one-page reference guide for helping you to explore chords yourself. Although there are a lot of chord names out there, you can actually become very proficient by understanding the general rules and learning to construct chords yourself.