Bar chords are among the most useful things you can learn to play. Although they can be hard at first, once you’ve built up the necessary strength and technique required, you will have access to more chords than you know what to do with.

This lesson is technically the second lesson, in a series about chords. In the first lesson, we explored open chords, and looked at the basic building blocks of Major and minor chords. In this lesson, we’re going to explore bar chords – what they are, why they’re useful, and how to play them.

Before we jump right into the nuts and bolts of this lesson, it would be very useful to describe what we mean by the word ‘bar’, and go through a few technical examples.

Firstly, ‘bar chords’ are often referred to as ‘barre chords’. Actually, barre chords is probably a more technically correct name, but ‘bar’ is simpler, so I’m going to go with that.

‘Barring’ a fret simply means playing multiple notes simultaneously using one finger, in the same fret. To do this we flatten one finger (usually the 1st finger), so that it forms a ‘bar’. Have a look at the following image.

As you can see, the first finger is covering multiple strings. When we want to play one string with one finger, we use the tip of the finger to push down on the string. When we want to play multiple strings with one finger, we ‘bar’ the finger.

The above image demonstrates a good exercise to practise when developing bar chord technique and strength. Simply bar an entire fret, and try to make the notes ring clear. The first time you attempt to do this, the sound that you produce will most likely be muted and rough, but just by working on this basic exercise, you will be building up the strength needed to play bar chords properly.

We’ll dive further into the technical side of playing bar chords shortly, but before we go on, we need to revisit open chords, and explore their limitations.

The Limitations of Open Chords

I’m assuming that you are already familiar with open chords, can play them relatively comfortably, and know how to read chord diagrams. If this is not the case, then you might want to go back and explore open chords before moving on to this lesson. You can brush up on open chords by reading the following lessons:

- What are Open Chords (1st lesson in this series)

- How to Read Chord Diagrams

- Chords Index Page (links to more lessons)

As a brief summary, open chords are simply chords that contain at least one open string.

One of the perks of learning things on the guitar is that often when we learn to play something, we can easily transpose it to a new key simply by moving along the fretboard and playing the same thing. This applies to chords, scales and arpeggios. If we play the B Major scale, starting on the 7th fret, we can use the same scale shape to play the Bb Major scale, starting on the 6th fret.

Chords are no different. Unless of course, they involve open strings.

Let’s look at the C Major chord, for example.

If we were to move the shape up by one fret, it would look like this.

According to the theory that everything on the guitar can be moved around, simply by moving frets, this should become a C# Major chord, right? Not really. The problem with the above example, is that everything hasn’t moved. The open notes have stayed right where they were. While our fingered notes have moved around, the open strings have stayed in exactly the same place. Therefore we have effectively changed the ‘shape’ of the chord and turned it into something completely different.

In fact, if you play the above chord, including the open notes, you get a pretty ugly sound. This does not always happen when moving open shapes around. For example, if you move that same shape up one more fret (so that the first finger is on the 3rd fret of the B string) the sound is quite beautiful. But it’s no longer the same chord that you started with, or even a transposition of the same chord, it’s an entirely different chord altogether.

So What’s The Solution?

As you’ve probably guessed, the solution is to ‘bar’ an entire fret of the guitar. By doing this you are effectively turning your barring finger into a capo.

Let’s take the C Major chord we were looking at and move it along one fret. The only difference will be that this time, we will ‘bar’ the first fret, so that there are no open strings.

It will look like this:

As you can see, the original ‘shape’ is still there, but there are now extra fingered notes, all played by the first finger (as a ‘bar’). Of course, we have to change the fingering of the original shape, so that the first finger is free to play the bar, but the original shape is still there none the less. In the above diagram, the ‘bar’ notes have been highlighted, to make the example more clear. As you might have already figured out, the bar itself is only producing two notes (1st string and 3rd string), because the 6th string is not being played, and the other three strings (5th, 4th and 2nd) are being played by other fingers.

Because of this, we can actually shorten the length of our ‘bar’, and simply cover the first three strings.

To simplify this even further, bar chord charts usually only include the barred notes on the strings that aren’t being played by other fingers. So in the above example, the first finger would not appear on the 2nd string, because that is being played by the second finger: Of course, the bar still needs to be played from the 3rd string to the 1st string, but in the above diagram, the first finger only appears on the 1st string and the 3rd string. Sometimes, to make this a little more obvious (that a bar needs to be formed) a curved line is used to indicate a bar, like this:

However, it should always be obvious if there is a bar involved, as it’s the only way to play multiple strings with the same finger.

So, now that we have now turned our original open C Major chord into a bar chord, we can move it freely around the fretboard. We can do this because there are no longer any open notes.

We could play it starting on the 5th fret, for example:

Or starting on the 8th fret:

This might be an obvious point, but it’s important to note that we haven’t just eliminated the open notes and replaced them with nothing. We have actually replaced them with the notes that are now being played by the barring finger. It can help to think of open notes as fretted notes, with the open notes effectively being ‘zeros’. Therefore, if you were to play all the open strings by themselves, like this:

…you could effectively move them up a fret by playing a bar:

…and then move them up another fret again:

This is what we’re doing when we play bar chords, we’re replacing the zeros with a ‘bar’, so that we can transpose chords by moving them around.

So let’s go back to the first bar chord shape that we produced, using the standard C Major open chord shape:

This shape is sometime used, but is definitely not a ‘common’ bar chord. Just like there are common open chords that are used disproportionately more than other open chords, there are certain bar chords that are used more often than other bar chords. We used the open C Major shape for the sake of doing an example, but in fact, there are four main bar chord shapes that we use much more than anything else.

That’s right, this whole introduction has been designed to introduce you to four bar chord shapes.

The Most Common Four Bar Chord Shapes

Major

Minor

Major

Minor

Root 6 Bar Chords

Let’s look more closely at the most common bar chord. It looks like this:

This chord is a ‘Major chord’.

As you might have figured out by looking at the above shape, this shape is effectively the open E chord shape, with a bar added to it.

This is worth observing, but in practical terms, it is actually not very important. You do not need to associate it with the E chord, you can simply remember it as a (Major) bar chord shape in its own right.

The beauty of bar chords is in the ability to transpose them by moving them up and down the fretboard. With the one shape that we have just looked at, you can play every major chord that exists. Want to play a G major chord? Simply play the shape starting on the 3rd fret. Want to play a Bb major chord? Simply play the shape starting on the 6th fret. There are twelve different possible Major chords. With this one bar chord shape, you have access to all twelve. Cool huh?

Once you can play the shape, moving it around is not hard. The challenge is knowing which exact chord you are playing, based on where you are on the fretboard. To do this, we need to go back the phrase in the above subheading – ‘Root 6 Bar Chords’.

‘Root 6’ simply means that the root note of the chord is on the 6th string.

If you’re unsure what the ‘root note’ of a chord is, think of it as being the ‘home’ note of a chord (or scale or arpeggio). When we play a ‘B’ Major chord, the root note is ‘B’. When we play a ‘B’ minor chord, the root note is still ‘B’. When we play a ‘Db’ Augmented 7 chord, the root note is ‘Db’. It is the main ‘root’ of the chord, upon which the other notes are built.

With ‘Root 6’ Major bar chord shapes, the 6th string tells us which actual major chord we are playing . Let’s look at the following diagram.

Here you can see that the root note (the highlighted one) is on the 6th string. It is also played up the octave on the 4th string and up another octave on the 1st string (highlighted again). So it should really look like this:

We only need to focus on one of the root notes, and the most obvious one is the 6th string, because that’s also the lowest note (pitch-wise) of the chord. So let’s go back to the first diagram:

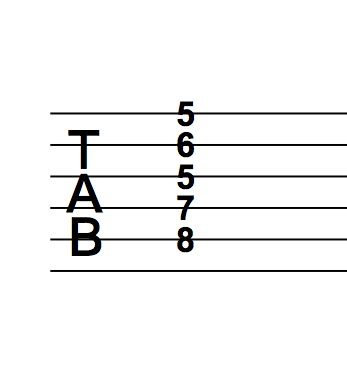

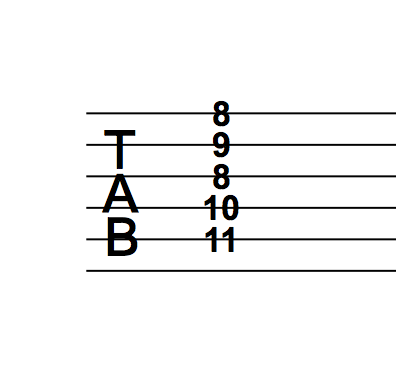

Let’s do an example. The 5th fret of the 6th string is the note ‘A’. Therefore, if we play the bar chord starting on the 5th fret (so that our first finger is barring the 5th fret and the note ‘A’ is being played on the 6th string), we will be playing the A Major chord:

The 8th fret of the 6th string is the note ‘C’. Therefor, if we play the same shape while barring the 8th fret, we are playing the chord C Major.

Therefore, all we need to know in order to move our bar chord around, are the notes along the 6th string. We’ll come back to this soon, but first let’s add another shape into the mix.

In the first lesson in this series, we learnt that Major and minor chords are the main two types of chords that exist. Therefore, the logical place to start with bar chords is to learn both the Major and minor shapes.

You’ve already learnt the Root 6 Major bar chord, here is the Root 6 version of the minor chord:

With these two shapes, you can literally play every major chord and every minor chord there is. This is quite a powerful tool to possess. It means you can theoretically play the chords for any song that uses only minor and Major chords (which is most songs).

Because these shapes are ‘moveable’, in order to use them practically, you need to know which chord you are actually playing (Cm, Dm, Bbm etc.) based on where you are on the fretboard. Therefore, you need to be familiar with the 6th string. As already mentioned, this is because the 6th string is where the root note is.

As a bit of a side note, I strongly recommend that you become familiar with the notes on the fretboard. It is one of the most underrated skills on the guitar. What’s more, you can achieve this skill quite easily, regardless of what level of ability you are currently at. Knowing the notes on the fretboard requires no technical ability whatsoever. It simply involves learning the system, and then testing yourself.

You can read about how to become familiar with the fretboard notes here. It’s not hard. For now, here is a basic table outlining the natural notes (no sharps or flats) along the 6th string.

The sharps and flats have been omitted, because if you know where the natural notes are, sharps and flats are easily derived from these (sharp = move up one fret, flat = move down one fret). Again, click on the above link if you need more help with this.

Here is the basic table:

Here are the two bar chord shapes we have learned so far:

Playing specific bar chords is simply a matter of playing either the minor or Major shape, and playing the shape in the right position, based on the root note that is required.

Here are some examples:

If you want to play the G minor chord:

Play the minor shape, with the the first finger barring the 3rd fret (so that the root note on the 6th string is G).

If you want to play B (major):

Play the Major shape, with the the first finger barring the 7th fret (so that the root note on the 6th string is B).

If you want to play Ab minor:

Play the minor shape, with the the first finger barring the 4th fret (so that the root note on the 6th string is Ab).

With two bar chord shapes, and knowledge of the 6th string of the guitar, you can literally play every Major and minor chord that there is.

How To Master Bar Chords

One of the early challenges with learning bar chords is that they require a certain amount of strength in the left hand to make the notes ring out. Simply being able to hold down a bar chord, and have every note of the chord ring clearly, can take weeks (or even months) of practice. This shouldn’t discourage you from practising them, and using them in songs. I often see students who get into a self-defeating loop; they struggle to play bar chords clearly, and find it physically tiring, so they stop playing them altogether. This of course means that they never improve, get discouraged, and declare that they “can’t play bar chords”. It sounds obvious, but if you are struggling, you have to keep practising, even when you feel like you’re not getting immediate results. Because there are muscles involved, you need to pace yourself, and be consistent over time, rather than trying to master them in a few sessions.

Mix Open Chords With Bar Chords

A good way to start using bar chords is to mix them in with open chords, especially if you are finding them particularly challenging. For example, the following exercise uses the chords A Major, F# minor, D Major and E Major.

By playing A, D and E as open chords, and F# minor as a bar chord, you can ‘ease in’ to bar chords and work your way up. Remember, you can take any song you know that uses open chords and simply substitute the open chords for bar chords. This is worth doing just to compare versions of the same chord (for example, how does the open chord version of A Major sound compared to a bar chord version of A Major?).

Root 5 Bar Chords

So far, we have learned two bar shapes (Major and minor). Both of these shapes are movable across the fretboard, and take their root note from the 6th string.

We are now going to look two new shapes, which take the root note from the 5th string.

The original root 6 major bar chord is effectively derived from the E major open chord.

The root 5 major chord is effectively derived from the open A major chord.

By taking the open A major chord shape, and putting a bar behind it, you get the root 5 major chord shape.

We can then modify this root 5 major chord, to get the root 5 minor chord.

As you can see, with both of these new shapes, the root note is played on the 5th string. Which is why they are called ‘Root 5’ bar chords. Just like the root 6 bar chords, you can move these up and down the fretboard, but this time, you need to be familiar with the notes along the 5th string (did I mention it was valuable to know the notes along the fretboard?).

Also, since the root 5 bar chords do not use the 6th string, you should only extend your barred finger over five strings (not six). While you could theoretically bar all of the strings and just try to strum five strings, this is what I would call a bad technical habit, and should be avoided, generally speaking.

Here are the notes along the 5th string:

Putting It All Together

Learning the Root 5 bar chords is very much the process as learning the Root 6 bar chords. You can work them into songs as much or as little as you want, by mixing them with open chords, or playing entire songs using just bar chords.

Another thing worth mentioning, is that even when playing a song using only bar chords, you now have options. For every chord that you choose to play as a bar chord, there is a Root 6 option and a Root 5 option. Need to play a Db minor chord? You can play the Root 6 minor shape on the 9th fret, or you can play the Root 5 minor shape on the 4th fret. Want to play the B major chord? You can play the Root 5 major shape on the 2nd fret, or the Root 6 major shape on the 7th fret.

This can be a little confusing at first, but keep in mind that this is actually the benefit of learning both Root 6 and Root 5 bar chords. By having two options for each chord, you can effectively choose combinations of chords that allow you to stay in a relatively small area of the guitar (if that’s what you want to do). Let’s look at the following chord progression, for example:

If we were to play this using only Root 6 chords, this is how it would look:

If we were to play this using only Root 5 chords, this is how it would look:

By using a combination of root 6 and root 5 bar chords, we can play the same chord progression, and stay in one general area of the fretboard:

Here’s another way we could play it:

Arranging the chords in a way so that you stick to one area of the guitar makes things easier to play, but it can also sound better, because the chords can sound more connected (although sometimes you may want the sound of big movements).

Using just two Root 6 bar chord shapes (Major and minor), and staying within the first 12 frets of the guitar (one octave), gives you 24 possible chords. If you add the two Root 5 shapes, you have an alternate version of each one of those 24 chords. That’s 48 possibilities with just four shapes!

Root 5 Major Alternative

Before we move on, it’s worth mentioning that there is an alternative, yet very common way of playing the Root 5 major chord. The shape that we have used so far, uses all four fingers of the left hand, including a ‘bar’ with the 1st finger:

Another way of playing this chord is to actually get rid of the bar with the 1st finger, and instead bar the 3rd finger:

As you can see, because the 3rd finger is now playing three notes, we can get rid of the 2nd and 4th fingers. The thing you need to avoid, when using this fingering, is playing the 1st string with your 3rd finger (the finger now doing the barring).

That’s because the extra note that is played by incorrectly fingering the 1st string is not part of the Major chord. Instead, what you need to do is lift your 3rd finger just slightly at the 1st string, so that the 1st string is muted.

Also, because the 1st string is no longer being played, there is no need to bar the 1st finger. The 1st finger can now simply play the root note, on the 5th string (see the chord shape above).

Minor 7 and Dominant 7 Shapes

The last thing we’re going to look at in this lesson are two more chord types – minor 7 and dominant 7 chords.

They’re included in this lesson on bar chords, because, although less common, they are often used with Major and minor bar chords, and are closely related.

In the previous lesson, we looked at the individual properties of Major and minor chords. Remember, chords are built using major scales. For example:

- Major chord = 1, 3, 5 (1st note, 3rd note, 5th note of the major scale)

- minor chord = 1, b3, 5 (1st note, flat 3rd note, 5th note of the major scale)

These new chords are built upon the major and minor chords that you have learnt, but each have an extra note of the scale:

- Dominant 7 = 1, 3, 5, b7 (like the Major chord, with the flat 7th note of the Major scale included)

- Minor 7 = 1, b3, 5, b7 (like the minor chord, with the flat 7th note of the Major scale included)

We’re not going to dive too deep into the theory behind chords just yet, as we will do that in an upcoming lesson in this series of lessons. For now, we’re going to focus on the shapes themselves. Here they are:

Dominant 7 (Root 6)

Minor 7 (Root 6)

Dominant 7 (Root 5)

Minor 7 (Root 5)

Root 6 Bar Chords

The dominant 7 chord often gets shortened in name to simply ‘7’. For example, A dominant 7 becomes ‘A7’, D flat dominant 7 becomes ‘Db7’, and so on. This is an important point, because you will rarely see a chord written down as a ‘dominant 7’ chord. Instead, you will most likely come across the abbreviated label.

As you can see, these new shapes are quite similar to the Major and minor shapes that we learnt earlier in this lesson. Just as with the Major and minor shapes that we’ve already looked at, you should practise these new shapes and be able to play them up and down the fretboard. While the minor 7 and dominant 7 are not as common as the Major and minor chords, they are relatively common, and because of their similarity in shape and sound to the Major and minor chords, it’s good to learn them as part of the ‘set’.

Bar Chords Summary

So far in this lesson, you’ve learnt eight different bar chord shapes, and how they can be moved along the fretboard. Here is a visual summary of the shapes, as well as the notes on the 5th and 6th strings:

Major (Root 6)

Major (Root 5)

Minor (Root 6)

Minor (Root 5)

Dominant 7 (Root 6)

Dominant 7(Root 5)

Minor 7 (Root 6)

Minor 7(Root 5)

Natural Notes Along The 6th String (E)

Natural Notes Along The 5th String (A)

Tips On Playing Bar Chords

- Go slowly. It can take a while to build enough strength in the hand to be able to play these chords well.

- Practise them every day. The strength and technique that is required to play these chords gets built over time. Just like developing any other muscle, you can’t ‘cram’ this work. You have to build it up consistently over time.

- When starting out with bar chords, use them in songs with open chords. This will allow you to ease in to them.

- Learn the notes along the 5th and 6th strings, as these two strings provide navigation for where to play bar chords. The first step towards learning the notes is learning the system.

- Play individual bar chords often in isolation, to test the strength and clarity of individual chords. When you are doing this, arpeggiate the chord (play each string one at a time), so that you can easily identify any weak spots.

- Play songs you already know with open chords, and substitute the regular open chords with bar chords.

- Learn new songs while limiting yourself to only Root 6 bar chords. Then do the same with just Root 5 bar chords. Then of course, combine them together.