The guitar is a strange instrument. The fretboard is really a collection of notes arranged in a kind of grid. There aren’t many instruments with which you can play the exact same note in a variety of ways. Take the piano for example. The notes are arranged in order of pitch. If you learn one octave of a piano, you basically know the whole piano. There’s only one key that you can press to play middle C. You can play C up an octave, or down an octave etc, but there is only one way to play each individual note.

Guitar is different. We can produce an E note by playing the open 1st string. We can also play that exact same note on the 5th fret of the 2nd string. Not a different octave, the same note (if you don’t know what an octave is, we will discuss that shortly). We can also play the exact same note on the 3rd string, on the 9th fret. Or the 14th fret of the 4th string. So what’s the point here? The point is that the layout of the guitar is unique, interesting and to many, unpredictable. Of course, once you know the system, the layout is very logical.

‘Knowing the fretboard’ is one of the most beneficial things a guitarist can do. It’s also one of the easiest. It is possible for someone to memorize the notes on the fretboard before ever having played even one note, because it is really just a matter of memory. If it is so easy and so important, why do so many players neglect to know their fretboard?

It’s probably just that it is easy to get away with not knowing. Getting to know the fretboard and memorizing things can be boring, so people often neglect it, in favor of learning the next ‘cool thing’. Also, the layout of the guitar makes it inherently easy to learn to play almost anything without necessarily knowing the notes involved. On the trumpet, when you are playing a C#, you know that you are playing a C#. On the guitar however, you can play something by relying only on string numbers and fret numbers (tabs anyone?).

What are Intervals?

Before we start really exploring the fretboard, we need to understand the basic concept of intervals. An interval is the distance in pitch, between two notes. In western music, the smallest distance between two notes is a semitone (actually, smaller intervals can be achieved by bending notes and other techniques, but I’m being general here). Exploring semitones on the guitar is very easy. Play any note on any string (don’t play open strings for now). Now move up one fret. You have just moved up a semitone. Now move up another fret. You have just moved up another semitone. The visual nature of the guitar makes it easy to see how intervals work. There are different labels given to different intervals, but the only two intervals we are concerned with in this lesson are the following:

- Semitone

- Tone

A semitone, is an interval of 1 fret. It is also known as a minor 2nd.

A tone is an interval of 2 frets (or 2 semitones). It is also known as a major 2nd.

It should be pointed out that technically speaking, using frets as a measurement is not the most comprehensive way of defining intervals. A semitone, for example, is really an interval relating to pitch, not frets. A semitone is a semitone on a piano, guitar, trumpet etc. Using frets is just an easy reference point to get started.

The Musical Alphabet

We’ll come back to intervals shortly. The other thing you must know, to master the fretboard, is the musical alphabet. What we really want to know here is, what range of notes actually exist?

The musical alphabet (not including sharps and flats) is this:

A, B, C, D, E, F, G (then it starts again at A)

These above notes can also be referred to as naturals, for example, ‘A natural, B natural’ etc. usually, we just refer to them as ‘A’ and ‘B’ etc.

Pretty simple right? It looks nice and clean and easy. This is only really half the story though. You’ve probably heard of the labels ‘Sharp’ and ‘Flat’ (for example ‘A Sharp’ or ‘D Flat’). These labels have symbols:

Let’s look at the musical alphabet with sharps (#) and flats (b) included:

- A

- Bb/A#

- B

- C

- Db/C#

- D

- Eb/D#

- E

- F

- F#/Gb

- G

- Ab/G#

- A (back to the start, up one octave)

Although it looks a little busier now, the above list is the entire range of notes available to us. The notes are written out in order, semitone by semitone. All of music is essentially an arrangement of these 12 notes.

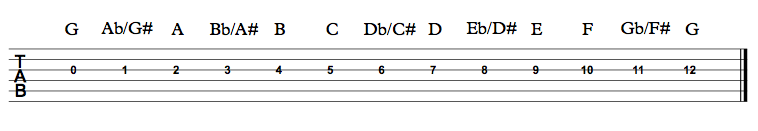

Let’s say you played an A note somewhere on the fretboard, for example, on the 5th fret of the 6th string. If you moved up a fret (to the 6th fret), you would now be playing a Bb (or A#). If you moved up one more fret (to the 7th fret), you would now be playing a B natural. The power of the above list should be apparent to you by now. If you know it, then given a starting note, you can get to any other note that you are looking for. Observe the following diagram:

In the above image, the open ‘G’ is the starting point, played as a ‘0’ on the 3rd string. Moving up one fret at a time (1 semitone), we simply go through each note of the musical alphabet.

This isn’t particularly difficult, exciting or complicated. But it’s very important. You should know it.

With this simple, yet important knowledge at hand, the task for learning the fretboard becomes pretty obvious – In order to ‘unlock’ the fretboard, you first need to understand the order of notes. If you know the musical alphabet, all you need is a starting note (such as the name of the open strings – which you already know) and you can figure out any other note.

A Bit More On Sharps And Flats

‘Sharps’ (#) are produced by moving a natural note up one semitone (one fret). For example, The note ‘A’, becomes ‘A#’ when moved up one semitone.

‘Flats’ (b) are produced by moving a natural note down one semitone (one fret). For example, the note ‘A’, becomes ‘Ab’ when moved down one semitone.

There is a distance of two frets (interval = tone) between most of the natural notes. For example, ‘B’ is a tone away from ‘A’. ‘E’ is a tone away from ‘D’. As you have probably figured out (or observed in the list of notes), all of the notes in between can be referred to as either a sharp or a flat, depending on which note is your reference point.

For example, there is a note in between A and B. This note is called A Sharp (A#) or B Flat (Bb).

There is a note in between D and E. This is called D# or Eb.

Put simply, for each ‘sharp’, there is an equivalent ‘flat’, and vice versa. This is known as enharmonic equivalence.

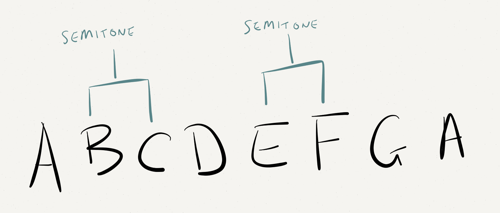

The tricky thing (again, you’ve probably already observed this) is that there is an interval of only one semitone between some natural notes. This occurs from ‘B’ to ‘C’, and from ‘E’ to ‘F’. Observe the full list of notes (above) that we looked at earlier to demonstrate this point. It is important to know this. Why does this happen? It doesn’t matter, it just does. When you get used to the order of notes, it feels normal.

Simplifying Everything

So we’ve covered the full list of notes, including sharps and flats. Just to summarize, this is what the list of notes (musical alphabet) looks like, with sharps and flats included:

- A

- Bb/A#

- B

- C

- Db/C#

- D

- Eb/D#

- E

- F

- F#/Gb

- G

- Ab/G#

- A (back to the start, up one octave)

With this information, as long as you have a starting point, you can figure out any note on the guitar (for example, start from B, move up a fret to C, then up another one to Db etc.)

The problem with the above list, is that it looks a bit too cluttered. Because you now know how to produce sharps and flats, it is easier to just remember the order of natural notes and also remember where the tones and semitones occur.

If you can commit these ‘rules’ to memory, you can figure out any note from a starting point. Since the semitone interval between 2 natural notes only occurs from ‘B’ to ‘C’, and ‘E’ to ‘F’. It’s even simpler to just remember where these intervals occur:

What Are Octaves?

What happens when we go through the twelve notes of the musical alphabet? We arrive at our starting note again, but up one ‘octave’. In the image above, we started from ‘A’, went through each note and then finished on ‘A’ again. It’s important to understand that the second ‘A’ is up one octave from the original. What this means is that it is effectively a higher-pitched version of the same note. Think of it like this – imagine a woman starts singing a song. Let’s say it’s ‘Happy Birthday’. Half way through, a guy joins in. Let’s assume that they are both singing perfectly in tune (a rarity, I know). What is most likely happening is that they are singing the same notes but one octave (or two) apart.

Octaves themselves are just intervals. As an exercise on the guitar, play any open string. Now play that same string on the 12th fret. You have just played the same note up one octave. You should be able to hear that they are effectively the same notes, but in a different range.

The 6th string and 1st string of the guitar are both ‘E’ notes. If you play them at the same time, you will hear that they blend perfectly with each other (because they are the same note). These two notes are two octaves apart from each other.

Starting From An Open Note

This may be obvious, but it’s also important to point out that the distance between an open note and the 1st fret is a semitone, just as the distance between the 1st fret and the 2nd fret is a semitone. If you think of it in numbers, an open note is a ‘0’, therefor ‘0’ to ‘1’ is one semitone (or one fret). ‘0’ to ‘2’ is two semitones (or two frets). This is worth pointing out because in order to figure out notes up and down the fretboard, you need a starting point. Since you know the names of the open strings (you learnt it in the first lesson), you can use these open strings as your starting point.

Memorizing The Notes:

We’ve spent quite a bit of time explaining the way that the ‘system’ works. This is important, because you need to be able to understand how the guitar is set out. Regardless of how long it takes you to figure out a note, it is empowering to know that you have the tools to be able to do so.

Ideally though, you want to be able to memorize where all the notes are, all over the fretboard, so that you can recognize any note, anywhere. This takes time, but like I mentioned earlier, it’s not particularly hard or complicated. There are a few things that you can do to speed up this process:

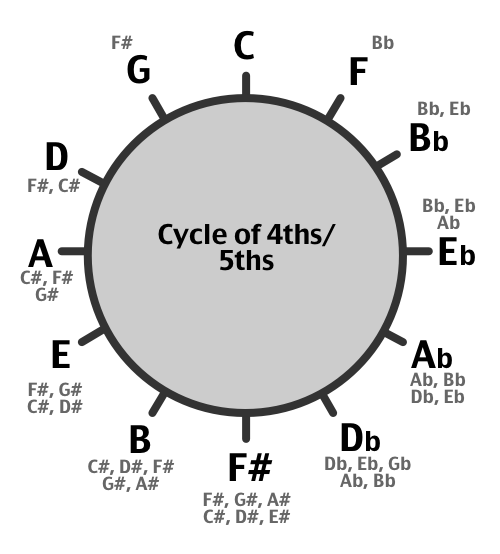

The Cycle of 4ths/5ths.

The ‘Cycle of 4ths/5ths’ is a tool that can be used for a range of applications. It is basically a circle, with the full list of notes arranged in intervals of 4ths (clockwise) and 5ths (counter-clockwise). Since we’ve overloaded our brains with intervals already, we’re not going to focus on theory relating to the cycle of 4ths/5ths, but we can still use it. The important things is that it contains all twelve notes in the musical alphabet. Here it is:

Sticking To One String

A great technique for learning the notes up and down the fretboard, is simply to take one string (such as the B string) and practice going around the cycle of 4ths (clockwise) and playing each note. Because you are sticking to only one string, you are forced to jump around and not rely on patterns. This is a very effective way of testing your knowledge of notes on the fretboard. When you feel you are getting confident with one string, move onto another. This isn’t a complicated method, but as I have already mentioned, ‘knowing the fretboard’ isn’t complicated or hard, it just takes time. Also, don’t worry about learning the notes beyond the 12th fret. The 12th fret is effectively where the notes ‘start again’. The 12th fret of each string is the same note as the open note of that string, up one octave. The entire range of notes are therefor contained within the first 12 frets. The notes beyond the that point are important, but they are effectively ‘doubles’ of the first 12 frets, so it’s best to limit yourself until you have memorized the first 12 frets.

Test Yourself

This isn’t so much an exercise as it is a state of awareness. Every guitarist loves to explore the guitar. Whenever you are exploring the guitar, improvising, or even learning a song, you can always ask yourself, ‘what note(s) am I playing?’. This is a very beneficial thing to do, as it is a way of prompting yourself to regularly identify notes and figure them out if you are unsure.

Using Notation

Perhaps the most effective way of learning the fretboard is to read music up and down the neck. This is probably the hardest method and can seem tedious at the start, but it is also the most effective. When you are reading notes in a certain position of the fretboard that you are unfamiliar with, having to constantly locate notes based on what you are reading creates a strong relationship between note names and the notes being played. Learning to read music across the entire fretboard is something that every guitarist should be able to do. The important thing when using this approach is to not use tabs. Tabs are great for other reasons, but if you are trying to force yourself to identify notes up and down the fretboard, tabs are a distraction.

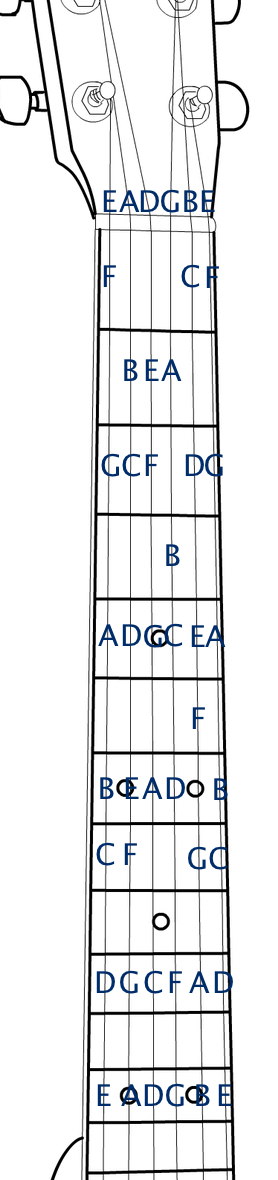

Picture Of Fretboard

The following image isn’t really necessary. You now know how to figure out any note on the fretboard. Just as a handy reference point however, I have included a picture of the fretboard with all the natural notes marked in (the sharps and flats are obvious if you know where the natural notes are).

Congratulations, you now have the keys to the fretboard. Use them wisely.