It’s time to enter the expansive world of scales. Scales are the entry point to a vast array of music knowledge, from chord theory, to song writing, to soloing and everything in between. Most people come across scales in some form or another quite early on in their guitar journey, even if they’re not sure exactly what they are or what their purpose is.

So What Are They?

The easiest way to think of a scale is as a set of intervals that create a particular sound which can be used for a range of purposes. In the previous lesson, we learnt about the ‘musical alphabet’ and intervals. Both are important for understanding scales. If you haven’t read the previous lesson, or you’re not confident with intervals and the musical alphabet, you can read the lesson here.

Major Scales

In this lesson, we are going to focus on the ‘Major Scale’. Major scales are the most important scale that you can learn. They are, in a way, the DNA of western music as we know it. We’ll discuss the importance of major scales a little more shortly. But for now, we want to know how to produce the major scale. The major scale is made up of the following intervals:

- Tone – Tone – Semitone – Tone – Tone – Tone – Semitone

The best way to try out this scale is to play the above set of intervals on one string. Playing a scale on one string is an easy to way to see how the scale looks from a visual perspective in its most simple format, while hearing how it sounds as well. In actual fact, we rarely play scales by using only one string, but it is a great exercise from a learning perspective.

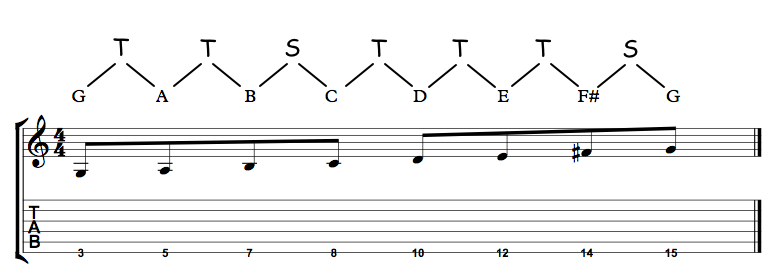

Let’s play the above scale (set of intervals) using only one string. Scales can be played starting from any note. The starting note determines what the ‘root note’ is. Let’s play the above intervals, starting on the 3rd fret of the 6th string. Because the starting note is G, we will be playing a ‘G major scale’. The starting note (in this case, G) is the ‘root note’.

The intervals are built upon the root note. Let’s look at the interval structure of a major scale again:

Tone – Tone – Semitone – Tone – Tone – Tone – Semitone

Now let’s apply that to the G major scale, starting on the 3rd fret of the 6th string:

- Starting Note (Root Note) – G (6th string, 3rd fret)

- Tone – A (6th string, 5th fret) – We have moved up a tone (2 frets) from G

- Tone – B (6th string, 7th fret) – We have moved up a tone (2 frets) from A

- Semitone – C (6th string, 8th fret) – We have moved up a semitone (1 fret) from B

- Tone – D (6th string, 10th fret) – We have moved up a tone (2 frets) from C

- Tone – E (6th string, 12th fret) – We have moved up a tone (2 frets) from D

- Tone – F# (6th string, 8th fret) – We have moved up a tone (2 frets) from E

- Semitone (back to the root note!) – G (6th string, 8th fret) – We have moved up a semitone (1 fret) from F#

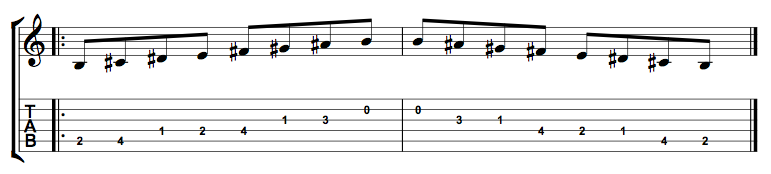

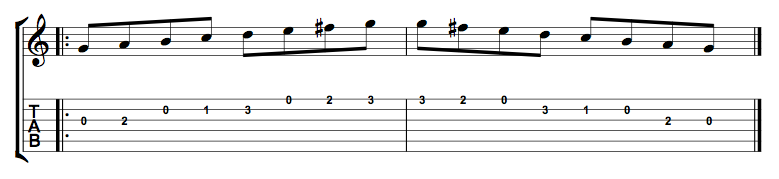

The above list of instructions makes it look more complicated than it is. But it’s good to be thorough. What we have just done, from a notation/tablature perspective, looks like this:

It sounds like this:

Hopefully you do not need to rely on the notes/tabs. It’s just for reenforcement. The interval structure of the major scale is simple to memorize and then play on one string. Once you have done it a few times, it should be very easy to pick a starting note (root note) and play the scale on one string. You don’t even technically need to be aware of which notes you are actually playing.

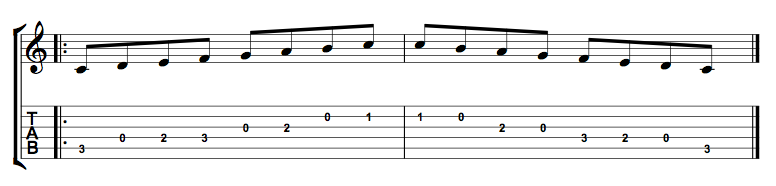

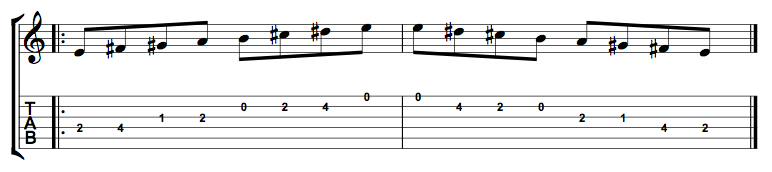

Let’s do one more example. This time we are going to play a C major scale, by starting on the 5th fret of the 3rd string. In the previous example, we only played the scale in one direction (ascending). In this example, we are going to play the scale ascending and then go back down the way we came (descending).

You should practice playing the major scale on one string, starting from different notes. You have probably realized that the sound of the major scale is familiar to you. This is because it is a very important scale that is kind of hard-wired into western music. You have probably heard it before, played as a scale, but also variations on the scale itself (for example, in the melody of a song).

Should You Know Note Names?

As you can see from the examples that we have done so far, major scales contain seven notes. The note names were written above each note to make things easier, but when you are practising scales by yourself, you won’t necessarily know what the note names are. Of course, you should know how to determine any note that you are playing, based on your knowledge of intervals and the musical alphabet that we covered in the last lesson. To start with, you should simply get comfortable playing the scale, using the intervals. Don’t worry about note names to start with while you get comfortable with the pattern and sound of the major scale as you practise it.

Once you are comfortable with playing the major scale on one string, the next step is to become familiar with the notes in each major scale. Knowing the notes holds the key to ‘keys’:

Major Scales And Keys

One of the most basic ways of demonstrating why major scales are important is by understanding what ‘keys’ are. When we play a song in a certain key, we are basically saying that there are certain notes (and chords etc) that we are going to use, because they belong in that key. This is a very simplified explanation, but that is essentially what a key is. Major scales are the things that determine which notes are in a key. If we are playing in the ‘key of A’, we are using the notes of the ‘A major scale‘. If we are playing in the ‘key of B’, we are using the notes of the ‘B major scale’ and so on. The major scale is like the ‘master scale’.

We have used intervals to determine what major scales are. This is a great way to get started and to quickly get a feel for what scales are. While we were playing major scales on one string, I said not to worry about note names because it was important to understand how to produce the scale quickly and easily, using intervals. Most of the time, however, we identify with major scales and keys by being familiar with the seven notes that are contained within the scale (and therefor that particular key). For example, the G major scale (we played this before) has the following seven notes:

G – A – B – C – D – E – F#

Therefor the notes in the ‘key of G’ are the same.

The C major scale has the following seven notes:

C – D – E – F – G – A – B

Therefor the notes in the ‘key of C’ are the same.

And so on and so forth.

Since there are twelve notes in the musical alphabet, there are only twelve keys to learn (not including enharmonically equivalent keys). So should you go through and figure out the notes for each key? You can. In fact, just for the sake of exercising your musical muscles, it is worth going through one or two keys, figuring out what each note of a particular scale is as you play them. It is a very good exercise to do. However, you don’t have to reinvent the wheel. Provided that you understand how major scales are constructed and how each major scale contains seven notes that determine its respective key, you can simply refer to a resource that tells you what the notes are in different keys.

Using Sharps And Flats

To make things even simpler, most of the time, we identify with keys by remembering which sharps/flats are in a particular key. When trying to remember the notes in a key, all you really need to ask is ‘what are the sharps/flats?’. For example, the key of F has a ‘B flat’. Therefor, we can assume that the rest of the notes are naturals. So the notes in the key of F are:

F – G – A – Bb – C – D – E

The key of D contains an F Sharp and a C Sharp. Therefor the notes in the key of D are:

D – E – F# – G – A – B – C#

Major Scales And Other Scales

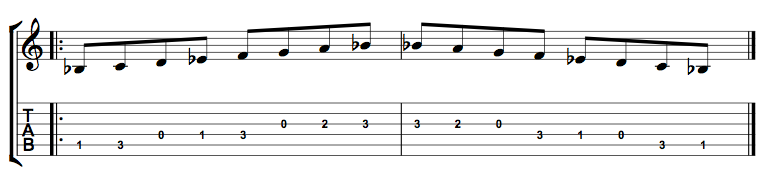

Another reason why major scales are so important, is that they are used as the basis for forming other scales. For example, we can produce a natural minor by lowering the 3rd note by a semitone, lowering the 6th note by a semitone and lowering the 7th note by a semitone. Therefor, if we wanted to play C natural minor scale, we could take the C major scale:

C – D – E – F – G – A – B

lower the 3rd, 6th and 7th by a semitone, and we would get:

C – D – Eb – F – G – Ab – Bb

If this is a bit confusing for you (after all, we’ve only just started on major scales), don’t worry. It has been included just to demonstrate that the major scale is indeed the ‘master scale’, and knowing major scales thoroughly is one of the best things that you can do if you want to be a smart guitarist.

Major Scales And Chords

Chords are formed by using notes from which scale? That’s right, you guessed it – the major scale. We are going to look at the structure of chords in another lesson, but in short, each chord has a unique set of notes relating to the major scale. The major chord for example is formed by taking the root note, 3rd note and 5th note of the major scale. The minor chord is formed by taking the root note, flat 3rd and 5th note of the major scale. Again, understanding chord theory is not important just yet. Simply knowing that major scales are important and how to play them is what you should aim for at the moment.

How To Really ‘Know’ Major Scales

We’ve covered the basics of what scales are and focused on major scales – how to play them and why they’re important. But how do you really become familiar with major scales? One of the best ways is to set yourself two goals:

- Be able to play the major scale in all 12 keys, in the open position

- Know the names of the notes in all 12 keys

If you can do this, your understanding of major scales will be awesome and the flow-on benefits in regards to learning other scales, chord theory, general theory etc. will be enormous.

Because you know how to figure out notes all over the fretboard (based on this previous lesson) and you know the interval structure of major scales (based on this current lesson), you already have the tools to figure out how to play the major scale in any key, and as I mentioned, it is a good exercise to try and figure out a few keys by yourself. But you don’t have to.

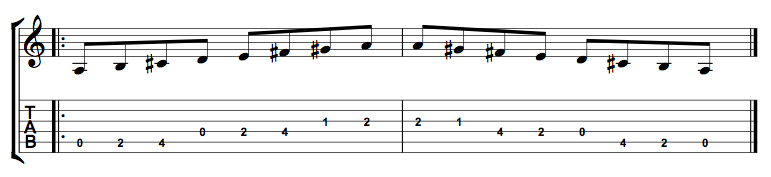

Right now we are going to look at the twelve major scales, played ascending and descending in the open position, over one octave. Remember, we explored scales by using only one string at a time, but in reality, we organize scales so that we can play them in certain positions.

With the following twelve major scales, you should practise playing them ascending and descending (as written) and also become familiar with the notes in each key. A really good exercise is to say the name of each note as you play it.

12 Major Scales:

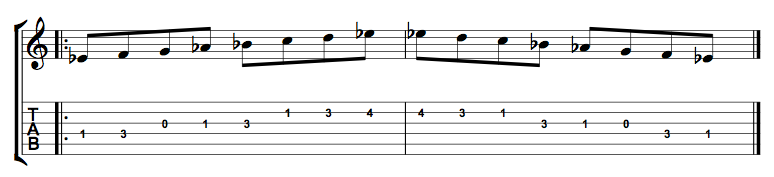

Key of C

The key of C has no sharps or flats. Therefor the notes in the key of C are:

C – D – E – F – G – A – B

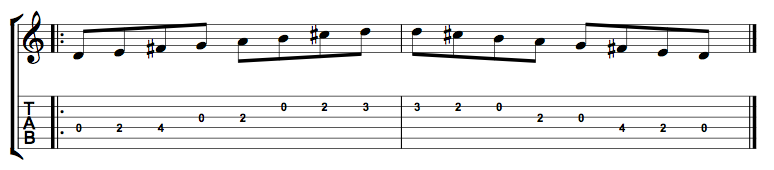

Key of F

The key of F has a B flat. Therefor the notes in the key of F are:

F – G – A – Bb – C – D – E

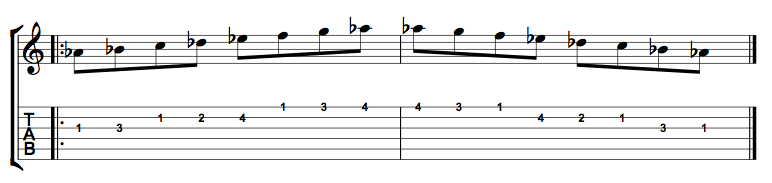

Key of Bb

The key of Bb contains B flat and E flat. Therefor the notes in the key of Bb are:

Bb – C – D – Eb – F – G – A

Key of Eb

The key of Eb contains E flat, A flat and B flat. Therefor the notes in the key of Eb are:

Eb – F – G – Ab – Bb – C – D

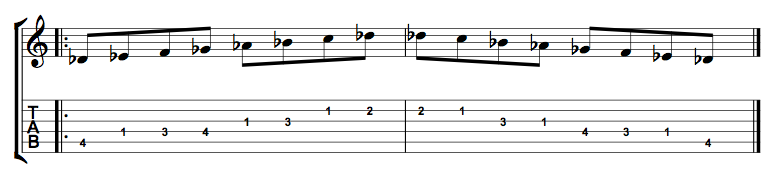

Key of Ab

The key of Ab contains A flat, B flat, Db and Eb. Therefor the notes in the key of Ab are:

Ab – Bb – C – Db – Eb – F – G

Key of Db

The key of Db contains D flat, E flat, G flat, A flat and B flat. Therefor the notes in the key of Db are:

Db – Eb – F – Gb – Ab – Bb – C

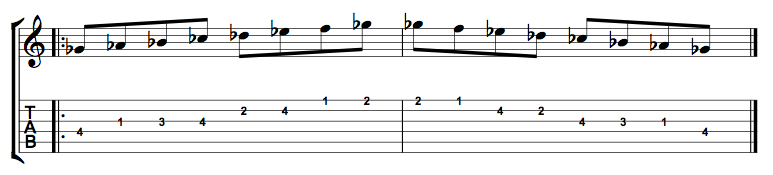

Key of Gb

The key of Gb contains G flat, A flat, B flat, C flat, D flat and E flat. Therefor the notes in the key of Gb are:

Gb – Ab – Bb – Cb – Db – Eb – F

Key of B

The key of B contains C sharp, D sharp, F sharp, G sharp and A sharp. Therefor the notes in the key of B are:

B – C# – D# – E – F# – G# – A#

Key of E

The key of E contains F sharp, G sharp, C sharp and D sharp. Therefor the notes in the key of E are:

E – F# – G# – A – B – C# – D#

Key of A

The key of A contains A sharp, C sharp, F sharp and G sharp. Therefor the notes in the key of A are:

A – B – C# – D – E – F# – G#

Key of D

The key of D contains F sharp and C sharp. Therefor the notes in the key of D are:

D – E – F# – G – A – B – C#

Key of G

The key of G contains F sharp. Therefor the notes in the key of G are:

G – A – B – C – D – E – F#

What About Enharmonically Equivalent Scales?

That’s the question you just asked right? In the previous lesson, we learnt that each flat has an equivalent sharp and vice versa. For example B flat is the same as A sharp, D sharp is the same as E flat.

So why have we only used one scale for every scale that could have been written two ways? Because the ones that have been used are much more common. You rarely come across a song in the key of ‘A sharp’, but B flat is very common. Since the B flat major scale and the A sharp major scale are essentially the same thing, I have included the one most commonly used.

Further Reading

Here are some links to more major scale related material. Some of it might be a bit tricky, but it can’t hurt checking it out!

Scales Page – This is the main scales page on the site. You will find links to lots of different scales. Not just major scales.