Why is a chord a chord? It’s a question philosophers have grappled with since the beginning of time. Ok, not really, but it is the subject of this lesson. Guitarists have a great dependence on chords. Many guitarists put themselves into the ‘rhythm-guitarist’ category and decide that that’s all they’ll ever learn. But for all the time we devote to learning chords and using them in music, we often overlook what they actually are, at a fundamental level. There are a few reasons why this happens. The main one is that we tend to learn shapes, which means that we can play a D minor chord without knowing what it’s made up of. We can also learn thousands of songs, using chords, without understanding how the chords work together, so we easy develop a philosophy early on of ‘Who cares why this chord works? It just does’.

But learning about chords opens up a world of possibilities for exploration and analysis. If you never analyse the chords you are playing, you’re missing out on a deeper understanding of how music works.

What Is A Chord?

A chord is technically any three or more notes played at the same time. There are almost infinite possibilities of note combinations that can be labeled as chords. But, there are really two main chords that outweigh the others in terms of importance and prominence.

The Major triad and the minor triad.

If you want to read an in depth lesson on triads, you can read the following lesson here, but as a brief summary, triads are simply three-note voicings. To understand how triads and chords work, you need to understand how the Major scale works.

The Major scale is made up of 7 notes, separated by intervals.

If we give each of the notes of the Major scale a number, it will look like this:

1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7

This is pretty simple stuff. The reason why it helps to assign numbers to each degree of the Major scale is that it helps to analyse triads.

The Major triad is simply the 1st, 3rd and 5th notes of any Major scale.

So for example, the C Major scale contains the following notes.

C – D – E – F – G – A – B

Therefor, the C Major triad contains C – E – G

The A Major scale contains the following notes

A – B – C# – D – E – F# – G#

Therefor, the A Major triad contains the notes A – C# – E

By taking the 1, 3 and 5, we are stacking notes in ‘3rds’. There is something that just works and sounds good when we stack notes in 3rds. If we were to take the first three notes (1, 2, 3) of the Major scale and play them together, it would sound cluttered and tense (perhaps it’s the sound you’re after). If we were to stack the scale in 4ths (1, 4, 7) it would sound harsh and tense. Thirds just work. You can try this yourself by experimenting with different note combinations.

The Major triad is made up of the 1, 3 and 5 of the Major scale. The minor triad is made up of the 1, b3 and 5 of the Major scale. Another way of looking at it is if we take the Major triad and lower the ‘3’ by a semitone, we get the minor triad.

Using our examples from before, the C Major triad is made up of

C – E – G

If we lower the ‘3’ (E) by a semitone (to Eb), we get

C – Eb – G

The A Major triad is made up of

A – C# – E

If we lower the ‘3’ (C#) by a semitone (to C), we get

A – C – E

So now we have two main chords

The Major triad (1 – 3 – 5)

The minor triad (1 – b3 – 5)

So why is this important? Because most of the time when we are playing chords, we are simply playing the Major triad or minor triad. When you play a D chord (for example), you are actually playing the D Major triad. We just call it D for short. When you are playing Em, you are actually playing an E minor triad. But if a triad is only made up of three notes, why is it that we strum six strings (and therefor six notes) when we play an E minor chord (or a G major chord etc)? This is because we’re doubling up on notes. The E minor chord is made up of the notes E, G and B. If we double up on any of these notes (by playing different octaves), we’re not changing the chord, we’re just giving the triad a fuller sound.

You can read more about exploring and playing triads in this lesson here. But the purpose of the explanation so far is just to explain what Major and minor triads are in theory, and how they are super important for understanding chords in general.

7 Chords In A Key

We’re now going to use our knowledge of triads and Major scales to see how chords fit together in a key. If you have even just a basic understanding of how to determine the chords in a given key, you will have an ability to make sense of thousands upon thousands of songs. It will give you a reference point for understanding and framing music in general. If you compose music (and you should), it will empower you with the ability to write chord progressions that just work and sound good.

The Major Scale

The Major scale is the master scale. When we talk about the notes in a key, we’re generally talking about the notes in a particular Major scale. When we build chords, we use the Major scale as our foundation.

Figuring out the chords in a key is simply a matter of stacking 3rds on each of the seven notes of the Major scale, to produce seven chords.

Let’s take the C Major scale for example.

C – D – E – F – G – A – B

If we stack thirds on top of C, we get the notes C, E and G. This is basically what we did before, when producing the C Major triad.

If we then go to the 2nd note of the scale (D) and stack thirds on that, we get D, F and A, which gives us the D minor triad.

Important – because we are in the key of C Major, we can only use the notes from the C Major scale, when stacking thirds on each note. If we took D in isolation, and stacked thirds using the D Major scale, we would get D, F# and A. But because we are using only notes from the C Major scale, we get D, F and A, which produces the D minor chord, because F is a semitone lower than F#.

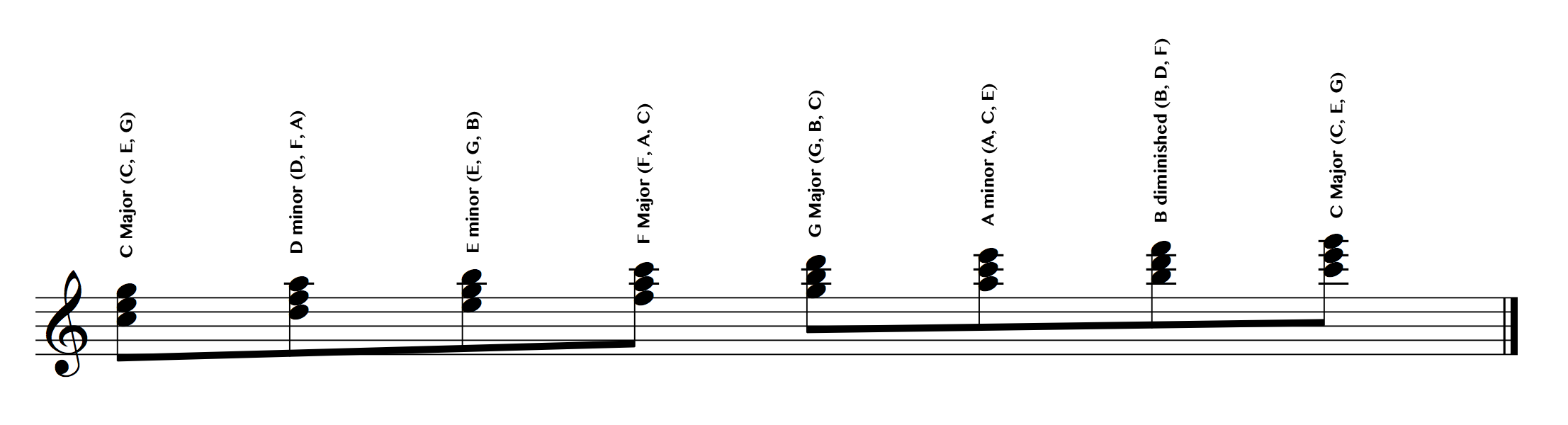

When we stack each of the notes in the C major scale using 3rds, we get the following:

As you can see, we have produced seven chords, one for each note of the C Major scale.

You should analyse the the picture above, and also play it yourself on the guitar. You can play it strictly as written, like this:

Or you can simply observe the chord labels and use the shapes that you are familiar with to produce each chord. You should notice that the strict triad version sounds a bit more organised and flowing. If you’re using a variety of shapes, it won’t necessarily sound as refined, yet it will still work adequately well.

Here’s another example using D major:

You might have noticed there is a pattern. Because the structure of the major scale does not change from key to key (it’s a set pattern of intervals), the chords produced when stacking 3rds will also produce a pattern, regardless of the key used. The pattern is a sequence of chord types. It looks like this:

- 1 – Major

- 2 – minor

- 3 – minor

- 4 – Major

- 5 – Major

- 6 – minor

- 7 – diminished

The above pattern is the basic formula for producing chords in any given key. If you memorise this pattern, and are familiar with Major scales (or can figure them out), you can figure out the seven chords in any key. Let’s do a few examples.

The notes in the key of E are:

E – F# – G# – A – B – C# – D#

Therefor, the chords in the key of E are:

E – F#m – G#m – A – B – C#m – D#dim

The notes in the key of F are:

F – G – A – Bb – C – D – E

Therefor, the chords in the key of F are:

F – Gm – Am – Bb – C – Dm – Edim

It’s that simple. You should experiment with figuring out a the chords in different keys. Write them out. You don’t need to stack the thirds – the formula will work. Just write out the notes of any Major scale on a piece of paper, add the chord types, then play through each chord to hear how they relate to each other and fit together.

It’s important that you play the chords on the guitar so that you become familiar with the sounds and moods that each chord produces. You can start out by playing each chord in sequence, one after the other, but you should then experiment with moving chords around. What you’ll find is that it’s extremely easy to produce chord progressions that sound musical. If you stick to the seven chords of any key, you can’t really go wrong. Each chord has a unique flavour and function, but relates to the other chords in the key. This is why it’s such a great tool for composition. With just this little bit of theory, you can compose meaningful chord progressions for the rest of your life. Experiment!

Roman Numerals

It’s important to point out, that when referring to chords in a key, roman numerals are often used. This is just a convention when discussing chords and chord theory. It’s pretty simple – the numbers from 1 – 7 become roman numerals, with the Major chords in uppercase, and the minor chords in lower case.

I – ii – iii – IV – V – vi – vii

Once you’ve become familiar with playing chords in a given key, you’ll probably notice that each chord has a certain function, or mood. These ‘moods’ are largely subjective, but just by analysing them, they help us become even more familiar with chords and music in general.

The I chord, for example, feels like the ‘home’ chord. This is the chord that whenever you return to, will sound resolved and safe. This means we can use it to resolve tension when our chord progressions need resolving. It also means that if we overuse it, we can arguably produce a chord progression that is bland or boring.

The V chord is the tension chord. The V chord wants to go back to the I chord. Experiment with playing different chords, then playing the second last chord as the V, then resolving back to the I. It should sound like the tension is peaking with the V chord, then resolving peacefully to the I chord. Of course, you could play the V, and then move to something else, which would create a sense of adventure, which might be exactly what you’re looking for.

Again, these explanations are very basic and the moods and roles of chords are largely subjective. But it’s really worth thinking about and analysing. By thinking about these things, you come up with an internal filter that allows you to appreciate and relate to chords on a much deeper level. It’s like many other things. Different wines taste pretty much the same to someone who has never drank wine before. But someone who has spent time analysing the tastes, smells and science of producing wine, will experience it in technicolours.

Names And Functions

Each chord in the Major scale has a name. These names are used mainly in classical music and help identify the function of each chord. The ‘Tonic’ for example, is the strongest chord in the key. The ‘Dominant’ is the second strongest chord etc. I don’t use these names very often. I prefer to refer to chords by their number. If you are interested, the names are below:

- Tonic (I)

- Supertonic (ii)

- Mediant (iii)

- Subdominant (IV)

- Dominant (V)

- Sumediant (vi)

- Leading Tone (vii)

Building Chord Progressions

Thinking about chords in roman numerals is a great way of identifying the function of chords. A great to explore the relationship between chords is to take a chord progression and apply it to different keys. Let’s look at the popular chord progression, known in jazz as a ‘2, 5, 1’:

We can play this chord progression in any key. Such as the key of C:

Or D:

You should play these chord exercises yourself, and apply them to other keys as well. You should hear that they are essentially the same thing, but are being played in different keys.

You should build new chord progressions yourself. A great way to approach this is to write out the seven chords in a key, then experiment until you find a chord progression that you like. Then write it out using roman numerals and transpose it into different keys.

Another popular chord progression is the following:

Try playing the above chord progression in as many keys as you can. Does it remind you of any songs that you already know?

Understanding chords in this fundamental way is empowering. You can literally compose thousands of songs with this basic theory. It gives you the ability to write chord progressions that make sense. It also gives you the ability to dissect music that you know and love and gives you a perspective to view it from.

There are a lot more areas for exploration now that you have broken down chords by stacking 3rds. You can more easily understand how modes work, for example. You can also construct four-note voicings using the same techniques that we used in this lesson.

We’ll cover four-note voicings in another lesson. For now, start making some chord progressions!