In the previous lesson, we discussed what chords are, why they’re amazing and we got started with playing a few shapes. In this lesson, we’re going to start playing some musical examples using chords.

To be able to use chords in a musical context, you need to be able to change from one chord to another. But you already did that in the previous lesson, right? Right, but to really make the chords come to life, you need to add two things to the equation.

Strumming and Rhythm

Strumming and rhythm are the backbone of chord playing. Chords by themselves are relatively meaningless tools. It is when we use rhythm to deliver the chords that they become music. With rhythm, we can take one or two chords and transform them into a piece of music. Most people have a good general understanding of what rhythm is, but we want to dig deeper. We’re going to deconstruct rhythm, starting with the pulse, so that we can make our chords come to life:

The Pulse

The most basic expression of rhythm is a pulse, or a beat. A pulse is simply what it implies, like the pulse of a heart. Let’s do an exercise. clap your hands at a slow but steady pace, while trying to keep the time between each clap the same. It should sound something like this:

This is a ‘pulse’, or a basic ‘beat’. You can hear it, but more importantly, you should be able to ‘feel’ it. It should feel like something is about to happen. Like you’ve just initiated a song that is about to kick into gear. Like you have a sudden inclination to dance, or at least move to the ‘beat’. This is what a pulse is. It is fundamental to more than 99% of the music that you will ever hear. The speed of the beat is measured in Beats Per Minute (or ‘BPM’). Literally, this is a measurement of how many beats occur within a minute. While different songs have different tempos (BPMs), most songs don’t change tempo from start to finish.

The Meter

Now that we know what a beat (pulse) is, we need to understand meter. In music, beats are organized into groups. The meter is also known as the time signature.

In more than 90% of music you hear, the beats are organized into groups of four. This is called 4/4. It is also known as ‘Common Time’. This recurring group of four beats provides a very important sense of momentum and symmetry. Here’s your next task: Count out loud the following:

1, 2, 3, 4, 1, 2, 3, 4

Just like the exercise before, make sure that the distance between each count is the same (keep the tempo even). You can even clap your hands with every count, just to maintain the continuity of the previous exercise. This should, to varying degrees, seem familiar. Most people have heard and imitated the rhythmic chant of “1 – 2 – 3 – 4” in countless (no pun intended) songs.

Keep doing the exercise. You should ‘feel’ a certain sense of momentum and symmetry that comes with grouping these beats into four. Why four? Why is four so common and so important to music as we know it? I’m not really sure. It just feels good. There’s probably a reason, but it really doesn’t matter. Each cycle of four, is called a ‘bar’ of music. Music notation is arranged in bars. It is a logical way to arrange a piece of music into smaller sections

If you want, you can experiment with other time signatures. Count to three repetitively in a similar fashion. This is the time signature of 3/4, the time signature used for waltzes. It feels different. While it is relatively common, it is by no means as common as the time signature of 4/4. Try doing the same for groups of five. This should feel a little bit strange, or odd. But don’t get too carried away just yet. For now, we will only be dealing with 4/4. Why? Because If you can master rhythms in 4/4, moving to another time signature is a pretty simple process. Trying to master different time signatures while learning about rhythm and strumming is unnecessary. You have my permission to pretend that 4/4 is the only time signature that has ever existed (for now).

Basic Rhythm

Now we are going to get into the fun stuff. Rhythm. We’ve established a pulse and organized each beat into infectious groups of four. The backbone of our hypothetical piece of music is well set. It is necessary to touch on an important point here though. While in our exercises so far, we have expressed the beat and meter by clapping and counting out loud, it is important to understand that the beat and meter continue throughout a song, even when we don’t express them audibly.

The beat and meter are the ‘backbone’ of any song. They repeat constantly from start to finish. Even when we do not express the beat and meter (by clapping or counting, for example), they still churn along underneath. Think of it like a blank canvass that can be used to produce music.

Do demonstrate this point, another exercise is in order. Let’s do the exercise that we did before. Count out loud (“1, 2, 3, 4”) repetitively. Only this time, clap your hands with every beat except for the 4th. Still count out loud on the 4th beat but don’t clap. This should give you a sense of the beat continuing, but the musical phrase (in this case, the claps) changing over the top. It should sound something like the following audio file. The audio file plays the cycle four times in a row.

To emphasize this point even more, do the exact same exercise again, but this time don’t count out loud, instead count only in your head. This is arguably a superior example, because it demonstrates (by counting in your head and not out loud) that the underlying beat and meter keep going even when they are not being played or heard.

This is really the whole principle behind rhythm and its relationship to the beat. The beat keeps going (perhaps silently, perhaps not), and we use it as a springboard for playing rhythms, by clapping, strumming, singing, or any other form of musical expression.

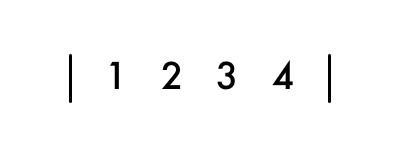

Let’s do some more exercises. This time, we’re going to use some visuals. Below is a bar of music, containing 4 beats (familiar stuff by now, right?). This is really just an exercise we’ve already done. Count out loud in cycles of 4 and clap on every beat. For each exercise, there will be an audio example that will play the exercise four times in a row.

For the next exercise, we’re going to count repetitively out loud to 4, but we are not going to clap on the grey number. Therefor, in the following exercise, we will only be clapping on the 1, 2 and 4. BUT, we must count for every number, even the 3, which does not get a clap assigned to it.

The next exercises are the same deal. Always count every beat, but only clap on the bold numbers, not the grey ones.

By now you should have grasped the general concept of rhythm. You are expressing different rhythms (by clapping) while using the beat and meter as your reference points. A good idea is to repeat the exercises, but count in your head (not out loud) while clapping the rhythms. This will allow you to really hear the rhythm of the claps. Remember, don’t just play each exercise once. Repeat them over and over again without a break in between, so as to really get a sense of the rhythm becoming established.

Strumming

So now you know what rhythm is, but what about chords? As I mentioned earlier, rhythm is an essential element of chord playing. Often, very few chords are used, but it is the rhythm that gives the chords musical interest. This is why chord playing is often referred to as rhythm guitar. So how do we execute rhythms when playing chords? With strumming. In the exercises which we have just done, we used clapping to execute rhythms. Let’s do the same exercises again, but with strumming.

So what is a strum? A strum of the guitar strings involves striking the strings one after the other with your right hand, in one quick motion. It sounds very much like all of the strings are being played at once, because it is a quick movement. In reality, each string is actually being played one at a time.

Down Strum

There are two types of strums – Down Strums and Up Strums. In this lesson, we will only be looking at down strums. Down strums involve striking the strings from the highest string (height-wise) to the lowest string. Let’s go back to our original exercises and strum the guitar instead of clapping. We are going to use an E chord for each of the following exercises. The E chord is a good example chord, because it involves all of the six strings. For chords with which not all of the strings are played (such as the D chord) there is a bit more technique required in ‘missing’ the unwanted strings.

Each of the following exercises is played using an E chord. The audio file for each exercise will play the exercise times in a row. As well as the usual counting, you will also hear a metronome in the background. You already know how important metronomes are, right?!

It should be pointed out that with the above recordings, each chord stayed ‘ringing’ until the next strum was strummed. This is not always the case. Sometimes we want to mute the strings during the space, but that is another technique that we don’t need to worry about just yet.

Changing Between Two Chords

In the last lesson you learnt about chords. In this lesson so far you have learnt about rhythm and strumming and applied it to one chord. Chords really come to life when you apply rhythm to chord changes. Chord changes, as the name suggests, involves changing from one chord to another. Changing between chords while maintaining steady rhythm is the hardest thing for a beginner to do when learning chords. It takes time. Your hands need to develop strength and technique which comes from regular practice. Also, keep in mind that when you practise one specific thing, you are building technique that will transfer to other things you learn. For example, spending a week working on the change from D to A will give you technique that makes the change from G to E easier (this is a fairly simple principle that can be applied to almost anything relating to skill and technique).

The easiest way to start working on chord changes is to use only two chords, choose a rhythm, and practise going continuously from one chord to the other. I think some exercises are in order…

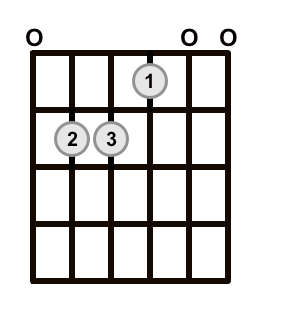

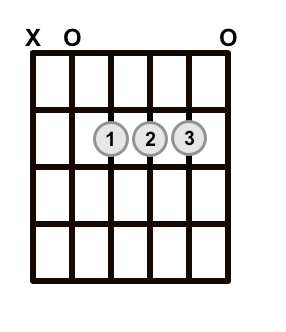

In the following examples, we are going to use the E and A chords. We learnt them in the previous lesson, but here they are again:

With each of the following rhythms, we are going to play E for two bars, then A for two bars. Then we are going to repeat the whole thing.

We are also going to use a ‘count-in’ with the following audio examples. A count-in is like an introduction that involves just counting. It serves a few purposes. Firstly, it sets up the tempo. Whenever you count-in, the tempo of the count-in should be the same tempo that will be used for whatever it is you are going to play. Also, it allows other people that you are playing with to know when to come in.

It’s effectively the musical equivalent of ‘ready, set, go!’. Most likely, you don’t need an explanation as to what a count-in is. You would have heard it before. It’s often deliberately used in songs as a sort of gimmick. The count-in that we are going to use goes like this:

1, 2, 3, 4, 1, 2, 3, 4

Any more explantations will probably make it seem more difficult than it is. Just listen to the audio examples and it should make sense.

Here is the first rhythm:

Here is how it sounds:

Obviously, this is a pretty simple rhythm with a strum only occurring on the first beat of every bar. This is a good one to do because it theoretically gives you more time to change to the next chord.

Let’s have a look at another two exercises:

We have used three simple rhythms here, but you should be able to hear how with rhythm and chord changes, it sounds like real music. The possibilities are endless. We have only used two chords. We can use a combination of any two chords, or add more. Of course, we could use different rhythms, or use one rhythm for one bar and then another rhythm for another bar. But you shouldn’t feel overwhelmed. The important thing to do at this early stage is to choose a simple rhythm (like the ones we just did) and practise moving from one chord to another. Always use a metronome (or play along with the recordings) and take it as slowly as you need.

One other thing to keep in mind is that the format in which the above rhythms is written in is not a standard way of writing rhythms (even if it is a perfectly clear and simple format). Writing rhythms using standard music notation requires a bit of theory that we haven’t covered yet (but we will in another lesson).

Moving On To Songs

Exercises are great for building technique and skill. You could theoretically take the information that you have learnt in these last two lessons and create exercises for yourself that you could play for months (and probably longer). But of course, playing the guitar is all about making music, so you want to start playing songs that you enjoy as soon as possible and start making music. There are thousands of songs that you can play with just a few chords, and learning them creates enjoyment, improves your ability, which then allows you to play even more songs. It’s a delicious cycle.

A Few More Notes

It should be said that we have really only scratched the surface with chord playing. While there is an almost infinite amount of material that can be played with what you have learnt so far, there are many other things relating to chords, rhythm and practise techniques that take a bit of explaining. But the purpose of this lesson series is really to give you the tools to get started

Further Reading

Now that we’ve covered a fair bit of material, you will often see supplementary lessons at the bottom of each lesson. What you will find are extra, optional lessons, related to material that we have just covered.

- Guitar Chords – This lesson doesn’t really contain anything that we haven’t covered in the last two lessons, but it’s a good summary of open chords that you should set out to learn.

- How To Strum – This lesson explores rhythm and strumming and goes into a bit more detail.

- Chord Construction – This lesson goes into detail about chord theory. Warning – there’s quite a bit of advanced theory here.