How do you use modes? It can take a lot of practice to understand modes and be able to play the shapes fluently by memory. Once you are starting to get on top of the basics, a greater challenge beckons – Using them in a music situation. This requires a broader understanding of modes. In this two-part lesson on using modes, we are going to look at the basics of using modes over a chord progression.

There are two approaches that we are going to explore in this lesson:

- Staying Diatonic

- Going Parallel

Staying Diatonic

I’m assuming for the sake of this lesson that you understand how modes are constructed, are pretty comfortable with playing the different modes in different keys and you are now looking for ways in which you can use the modes in musical situations. When we ‘staying diatonic’, what we are effectively doing is choosing the appropriate mode that fits over the given chord, based on the diatonic structure of a major scale. If you’re not sure what diatonic or functional harmony is, please read the following post on functional harmony. In fact, that lesson is pretty much a lesson on staying diatonic, so it’s a must read. Assuming you have read that article, or are already familiar with diatonic harmony, let’s recap what diatonic harmony is:

When we stack 3rds on each degree of the major scale, we get the following ‘set’ of chords:

I – Major 7 (1, 3, 5, 7)

ii – minor 7 (1, b3, 5, b7)

iii – minor 7 (1, b3, 5, b7)

IV – Major 7 (1, 3, 5, 7)

V – Dominant 7 (1, 3, 5, b7)

vi – minor 7 (1, b3, 5, b7)

vii – minor 7 flat 5 (1, b3, b5, b7)

When we look at the 7 modes of the major scale, we get the following:

I – Ionian (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7)

ii – Dorian (1, 2, b3, 4, 5, 6, b7)

iii – Phrygian (1, b2, b3, 4, 5, b6, b7)

IV – Lydian (1, 2, 3, #4, 5, 6, 7)

V – Mixolydian (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, b7)

vi – Aeolian (1, 2, b3, 4, 5, b6, b7)

vii – Locrian (1, b2, b3, 4, b5, b6, b7)

As you can see, each chord ‘fits’ over its respective mode and visa versa. This is the fundamental principle behind ‘staying diatonic’. Each chord of a key has a respective mode that is used over it. Again, if you don’t fully understand the concept of modes yet, read the article, guitar modes explained.

So we know that each chord in any given key has a mode that goes with it. What we want to do now is explore that idea in a real musical example so we can put the modes to the test.

Analyzing A Chord Progression – Finding The Key Center

One thing to keep in mind, is that when we are using modes – for solos, melodies etc, we usually already have a chord progression established. Usually, there’s a song or riff that we want to be able to construct solos over and we are looking for the best approach with regard to scales and modes. This is an important point, because what it means is that we need to be able to analyze chord progressions in order to establish which modes to use. Because modes and diatonic chords are constructed from the one major scale, our first task in analyzing a chord progression is finding the key center. Effectively what we’re asking here is “What key is this in”? It’s as simple as that. Let’s look at a few examples. We are firstly going to look at examples that do not modulate. In other words, chord progressions that remain in the same key.

Example 1:

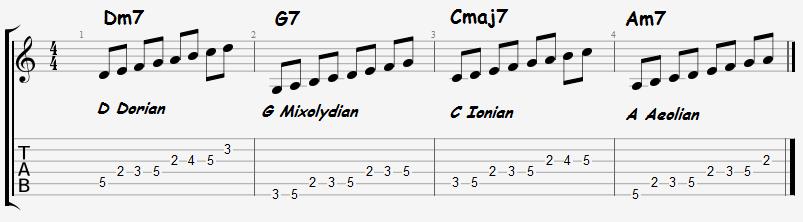

This first chord progression contains 4 bars with the following chords – Dm7, G7, Cmaj7, Am7.

This is a very simple way of writing a chord progression (let’s assume it’s in 4/4). It’s almost like a short hand way of writing, which can be quite common. The idea is to keep it simple while we analyze what’s going on. Remember, I’ve stated that the first few examples do not modulate – they do not move to a different key within the one chord progression. We want to determine the key center. In other words, we’re asking, “What key is this in?”, or “What major scale produces the diatonic chords that are represented here?”. There are a few ways to go about this. We could just look at the first chord, in this case Dm7 and figure out which keys contain Dm7. Dm7 is the ii chord of C major. It is the iii chord of Bb major. It is the vi chord of F major. We therefor have 3 keys that the above chord progression might be in. Of course, we need to check the other chords as well to determine which of these 3 keys is the ‘master’ key. It is essentially a process of elimination. Let’s look at the next chord, G7. G7 does fit into the key of C major. It does not fit into Bb major (Bb major produces Gm7) and it does not fit into F major (F major produces Gm7). Therefor, the key of C major is our only option. Let’s look at the diatonic chords in the key of C major just to be sure:

I – Cmaj7

ii – Dm7

iii – Em7

IV – Fmaj7

V – G7

vi – Am7

vii – Bm7(b5)

As you can see, the chord progression is in the key of C. the four chords (Dm7, G7, Cmaj7, Am7) are all diatonic chords in the key of C. We essentially used a process of elimination by starting with the first chord, then moving to the next, and so on.

Using Short Cuts

This process might seem a bit mundane and tedious to start with, but don’t be discouraged. Every time you do this process, you gain valuable experience in understanding of modes and diatonic theory. The other thing to keep in mind, is that after a while you start noticing patterns and short cuts. Simple things come easier, like knowing that Dm7 is in 3 keys. Or, for example, that there is only one dominant 7 chord in each key. The V chord in every key is a dominant 7 chord and it is the only dominant 7 chord (check the above list again). Why is this important? Because it means that if we see a dominant 7 chord in a chord progression, it will provide the quickest short cut to determining the key center. In our above example, there was a G dominant 7 chord (G7). G7 is the V chord in the key of C. No other key produces a G7 chord. Therefor, rather than using the process that we used originally (which worked), it would have been quicker, to scan the chord progression, observe the G7 chord, and go from there. This is just one example of little short cuts that can be used. You will find your own short cuts the more you practice.

So we have successfully analyzed the chord progression and found the key center. That allows us apply modes to that chord progression, which is what we ultimately want to do. How do we apply modes to chords? Well, now that we know that in every key, each chord effectively has a matching or corresponding mode, and we have determined the key center of this chord progression, we want to apply the appropriate mode to each chord”

Dm7 – this is the ii chord in the key of C major – therefor, we use the 2nd mode of C major – D dorian

G7 – this is the V chord in the key of C major – therefor, we use the 5th mode of C major – G mixolydian

Cmaj7 – this is the I chord in the key of C major – therefor, we use the 1st mode of C major – C ionian

Am7 – this is the vi chord in the key of C major – therefor, we use the 6th mode of C major – A aeolian

So now that we’ve matched up the modes to the chords, we need to actually use them in a musical way. This topic on it’s own could be talked about in endless detail, but for now, let’s keep it very simple. All we will do is play each mode in even 8th notes over each chord. It will sound a bit mechanical and ‘scale-ish’ but you will hear (if you try it yourself) that each mode fits perfectly with each chord:

What we are doing here is playing through each mode for the duration of one bar and then moving on to the next as the chord changes. It’s a very simple exercise, but it is the first step in using modes over chord progressions. This exercise is most effective when playing through the modes while the appropriate chord is being played as well so that you train your ears to hear how each mode fits over each chord. I would recommend recording the chords first, or entering them into a music editing program so that you can loop the chord progression and practice the modes over the top. Let’s look at another example:

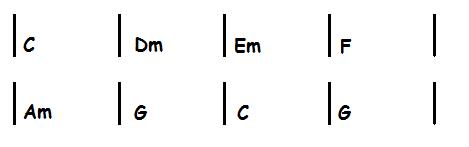

Example 2:

In this example, we have 8 bars of music, with one chord in each bar. This example does not use 7th chords, but the same process still applies. Let’s look at the first chord, C Major. If we are looking at triads, the chord C Major is the I chord in the key of C, the IV chord in the key of G and the V chord in the key of F. So far, there are 3 possibilities of keys – C, F, G. Let’s go to the next chord, D minor. D minor is the ii chord in the key of C and the vi chord in the key of F, but Dm does not exist in the diatonic key of G. Therefor, we are now down to two options – C and F. Lets look at the next chord, Em. Em is the iii chord in the key of C but the key of F has E diminished, not E minor, therefor the key of C is our only option. Let’s look at the diatonic triads in the key of C major:

I – C

ii – Dm

iii – Em IV – F

V – G

vi – Am

vii – B dim

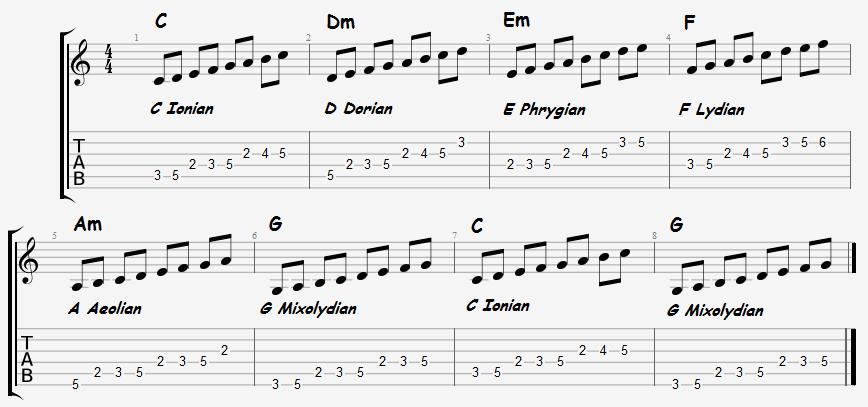

As you can see, each chord from this example fits in the key of C major. So now we will match up each chord with its corresponding mode and play through each mode for the entirety of the bar, just like before:

Again, it’s a matter of playing through the musical example using the modes as a way to familiarize yourself with the relationship between modes and chords. Let’s look at one more example of a chord progression that does not modulate outside of 1 key.

Example 3:

This chord progression uses both 7th chords and triads. When a chord progression uses both 7th chords and triads, the process for analyzing the chord progression is essentially the same. This is because a 7th chord contains the notes of a triad. For example, a Major 7 chord (1, 3, 5, 7) contains a Major triad (1, 3, 5).

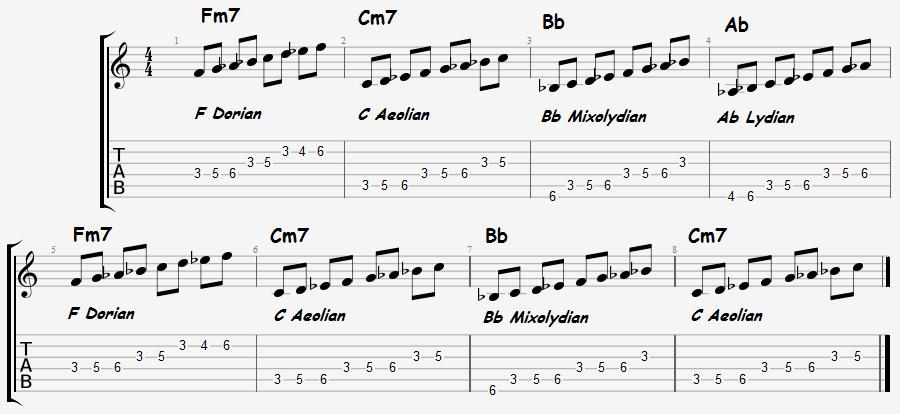

The first chord of this chord progression is Fm7. Fm7 is the ii chord of in the key of Eb, the iii chord in the key of Db and the vi chord in the key of Ab. The next chord, Cm7, is the vi chord in the key of Eb, the iii chord in the key of Ab, but it is not found in the key of Db. The 3rd chord Bb, is the V chord in the key of Eb, but is not found in the key of Ab, therefor Eb major is the key center of this chord progression.

Let’s look at the diatonic structure of Eb major:

I – Eb Major (triad) – Eb Major 7 (7th chord) – Eb Ionian (mode)

ii – F minor (triad) – F minor 7 (7th chord) – F Dorian (mode)

iii – G minor (triad) – G minor 7 (7th chord) – G Phrygian (mode)

IV – Ab Major (triad) – Ab major 7 (7th chord) – Ab Lydian (mode)

V – Bb Major (triad) – Bb dominant 7 (7th chord) – Bb Mixolydian (mode)

vi – C minor (triad) – C minor 7 (7th chord) – C Aeolian (mode)

vii – D diminished (triad) – D diminished 7 (7th chord) – D Locrian

Now let’s play the appropriate modes over each chord in the progression:

It is interesting to note that while the key center for this chord progression is Eb, there is no actual Eb chord in the chord progression.

Modulation – Key Changes

Now let’s look at a few examples of chord progressions that modulate. Modulation is when the key center of the chord progression changes within the one piece of music. We could talk about modulation in great length on it’s own, but the purpose of this lesson is not to discuss harmony in great detail, but rather how to analyze it and how to assign modes to chords within a harmonic progression.

The process for determining the key center, or key centers of a chord progression that modulates is essentially the same for that which does not modulate. The only caveat is that there are more possibilities because of the numerous key centers, which can make things a bit trickier. There can also be confusion relating to whether modulation has taken place, or the key center has simply not been found yet. For example, if the 3rd chord in a chord progression does not fit in the same key as the first 2 chords, does that mean that it has modulated, or does it just mean that what you thought was the key center for the first 2 chords was actually not the key center at all? Generally speaking, though, the process is the same, but a bit more attention to detail is often required.

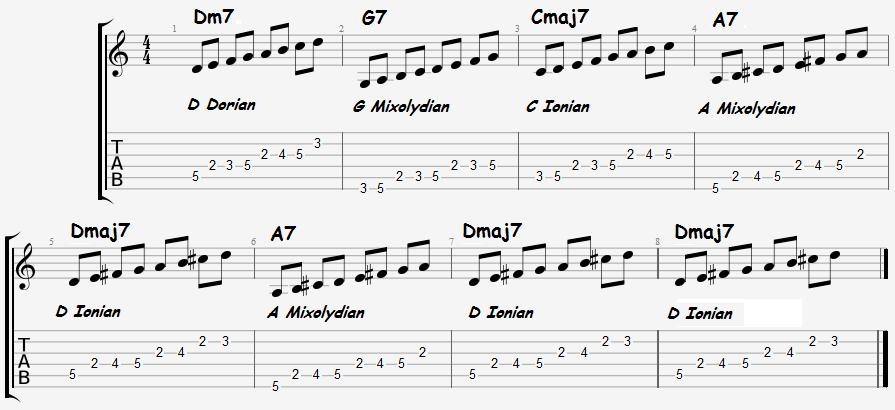

Let’s look at this first modulating example. The first two chords are Dm7 and G7. Because there is only one dominant 7 chord in each key center, we can use G7 as our starting point and then go from there. G dominant 7 is the V chord in the key of C major. Our first chord, Dm7 fits into the key of C major as it is the ii chord. Our 3rd chord, Cmaj7 is the I chord in the key of C major. Let’s keep going. The 4th chord is A dominant 7. As there is only one dominant 7 chord in each key, and G7 is the dominant 7 chord in our current key (C major), there is obviously modulation happening at this point. What is A7 the V chord of? The answer is the key of D major. Our 5th chord is Dmaj7. Dmaj7 is the I chord in the key of D. On to the next chord, A7. We’ve already determined that this belongs to the key of D major, as does the next chord, Dmaj7, which is in the 6th and 7th bar.

So, in summary, the first 3 chords are in the key of C major and the 4th chord modulates to the key of D major, where it stays for the remaining bars.

Just to make things a little less confusing, I’ll write out the diatonic chords in both the key of C and the key of D:

Key of C

I – Cmaj7

ii – Dm7

iii – Em7

IV – Fmaj7

V – G7

vi – Am7

vii – Bm7

Key of D

I – Dmaj7

ii – Em7

iii – F#m7

IV – Gmaj7

V – A7

vi – Bm7

vii – C#m7

You should be able to see that the first three chords can be found in the first list (Key of C) and the next five chords can be found in the second list (Key of D). How would we apply modes to this chord progression? Exactly the same as before when we were not modulating. The only difference is that now we are drawing modes from two different keys. Let’s produce another two lists but look at the diatonic modes of the key of C and D this time.

Key of C

I – C Ionian

ii – D Dorian

iii – E Phrygian

IV – F Lydian

V – G Mixolydian

vi – A Aeolian

vii – B Locrian

Key of D

I – D Ionian

ii – E Dorian

iii – F# Phrygian

IV – G Lydian

V – A Mixolydian

vi – B Aeolian

vii – C# Locrian

Now we are going to apply the modes to the chords in the same way that we did for the earlier examples. Each mode is played for 1 bar in constant 8th notes over the relevant chord:

It’s worth clarifying something at this point. We have said that we are going to look at modes from using two approaches – staying diatonic and going parallel. In the last example we have jumped in to the world of modulation. Does that mean we are moving away from staying diatonic? No! Staying diatonic refers to the way in which we apply the modes to the given chord progression. The fact that a chord progression modulates does not change this approach because the approach relates only to how we apply the modes itself. In part 2 of this lesson, going parallel, you will see the difference between the two approaches.

Let’s look at two more examples of chord progressions that modulate:

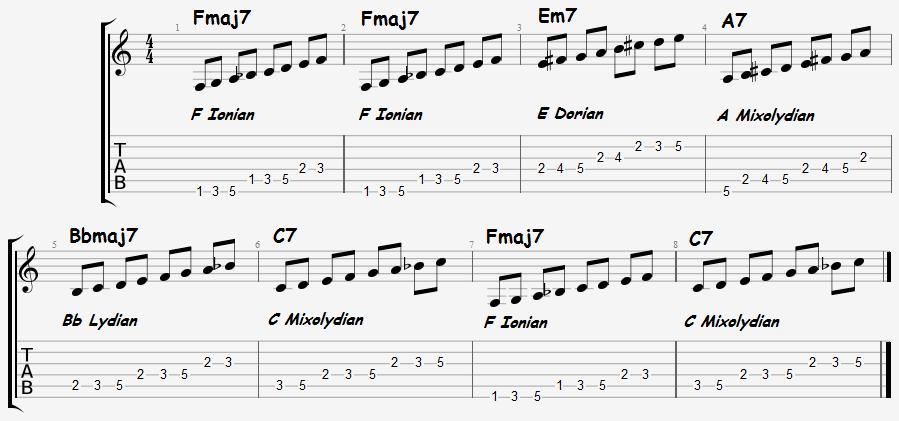

This is an interesting example. The first chord Fmaj7, could be the I chord in the key of F, or the IV chord in the key of C. Of course, the obvious thing to do is to look at the next chords for clues. In the 3rd bar (where the chord changes) we have Em7. This at first would suggest that we are in the key of C, as Em7 is the iii chord in the key of C but is not found in the key of F (instead we Em7b5 is found). While this might seem like an obvious choice, the next chord, A7, is the V chord in the key of D, which means that our Em7 chord could be interpreted as being the ii chord in the key of D. Which one is correct? Again, it’s hard to know for sure. Sometimes, there are multiple possibilities and more clues are found in other areas, such as the melody of the song. In this case however, we are only looking at the chords, so we need to make a decision. I would actually interpret the first two bars (Fmaj7) as being in the key of F and the next two bars as being in the key of D. There are a few ‘intuitive’ reasons for this, which come with experience. Firstly, it’s very common for a song to start with the I chord as it creates a sense of grounding. Also, the next line modulates to the key of F. Bbmaj7 is the IV chord of F, C7 is the V chord of F and Fmaj7 is the I chord of F. Therefor, as a lot of this chord progression is centered around the key of F major, it makes sense that the first chord is in the key of F major. Again, there are little clues and patterns that you look for when you get more experience doing this sort of thing. For now, if you come across a chord progression that presents ‘options’ and you are not sure which one to go with, just choose one that you feel comfortable with and it will work fine. Let’s now apply the modes to this chord progression. I won’t go into the theory behind every mode as that should be pretty clear by now. Just remember, the first two bars are in the key of F, the next two are in the key of D and then the next four are in the key of F:

Let’s look at one more example of a chord progression that modulates and then use modes over that progression:

This is another interesting chord progression that at points might seem a bit vague or confusing. The First chord is Cmaj7, which could be the I chord in the key of C, or the IV chord in the key of G. If we look at the next chord for clues (C7), we find that C7 is the V chord in the key of F, which means that we can’t technically be 100 percent sure of which key the first chord is in. It could be C, or it could be F. Just like before however, we will ‘choose’ the key of C major, as starting with the I chord is a common and musically safe thing to do. So the first chord (Cmaj7) is in the key of C. The second chord (C7) is in the key of F. The third chord (Fmaj7) is also in the key of F (the I chord). The 4th chord (Fm7) can not possibly be in the key of F major. So let’s look at the 5th chord, Cmaj7. There is no key that contains both Fm7 and Cmaj7. So in this chord progression, the Fm7 is really out on its own. Again, this means that the key is kind of indefinite, so we need to choose an appropriate key, based on which one we think works the best. Fm7 could be the ii chord of Eb major, the iii chord of Db major, or the vi chord of Ab major. We will go with the key of Eb major, as this is the closest key to the previous key of F major. Now let’s look at the second line. Out of the 4 chords here, 3 are in the key of C major (Cmaj7, Dm7, G7) and one chord (A7) is in the key of D.

Let’s now look at the appropriate modes over the chord progression:

In summary, a comfortable knowledge about diatonic chords and scales, using modes is quite straight forward, even if the process is time consuming at first. Remember, the process is half the fun at first. It’s fascinating to analyze songs and chord progressions and ‘unravel the code’. Of course, we haven’t really yet looked at applying the modes using important musical tools such as phrasing and voice leading. At the moment we are covering the fundamentals, but the fundamentals are very important.

Once you understand the concept of modes, functional harmony and chord/scale relationships, it’s time to move on to part II of this lesson on how to use modes – Going Parallel.